The Cyber-Fraud Hitting Alaska Airlines' Customers - And The Blame Pinned on Them

Follow my journey from armchair sleuth, to cyber investigator, to forensic accountant all the way to today where I stand as a neophyte short-seller.

The below represents my opinion based entirely on publicly available information, including U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings, public financial data, social media postings, and other public records. I have no inside information. I hold a short position in Alaska Air Group, Inc. ($ALK) and stand to profit from a decline in the share price. What follows is not investment advice. If you wish to skip the meanderings that follow and read the precise report they led to, you can find it here.

Act 1: A Riddle on LinkedIn

Alaska has been bothering me for a while. And it bothered me again this week. Not the state, which I’m sure is very nice, but the airline.

The Seattle Times ran an article the other week on Alaska Airlines’ customers having their miles robbed. It was the very same story I stumbled across on LinkedIn back in August.

Let me tell you why it bothered me then, and bothers me now.

The post was somewhat trivial. That’s not to denigrate the author. Life is trivial, and LinkedIn is a trivial place. A Mr. Bhuiyan was complaining about a poor consumer experience he’d had of late, which was resolved satisfactorily, to the credit of the firm involved.

I invite you to take a look (archive), but I’ll relate the essence of it here.

Someone stole 185K miles from my Alaska Mileage account.

I happen to log in to my Alaska Mileage Account and noticed a sharp decline in my available miles. Turns out, someone just today redeemed 185K miles from my account for biz class tickets: Doha to London. It wasn’t me. No idea how they were able to do this and neither does Alaska. But big shout to Alaska Airlines customer service team! They were able to credit back the miles within 40 mins.

Going forward, I do have to call their customer service and give a pin to book award tickets but it’s worth it for the peace of my mind.”_

The post included an image of a flight booked from in fact all the way from Guangzhou to London via Doha with Qatar Airways, in the name of a Mr. Xie.

When I looked at the comments, I found 48 unique responses. Twelve people, including Mr. Bhuiyan, reported being victims of the same theft. Of these twelve victims, five specifically praised Alaska’s customer service for the swift resolution. An additional eleven commentators, who had not been victims themselves, also praised Alaska’s handling of the situation. Though there was a chorus of requests for 2FA (Two-Factor Authentication) to make accounts secure.

Clearly, the just-in-time tickets are necessary to evade detection by the account owner. Presumably, the hacker re-sells these tickets on an illicit marketplace. Mr. Xie may or may not have been unaware of the provenance of his ticket.

None of this seemed logically possible, as it begged 3 mysterious questions:

Why, if this is a common problem for Alaska, do they not bring in 2FA? Or a host of other cyber-defences that would stop this?

Why is the victim being forced to inconveniently call in and give a PIN for future bookings when the errant password has been changed? But most of all....

Mr. Xie! What a reckless gambler! A knock-off flight saving him a few thousand, but the gauntlet he had to run. Facial recognition at Guangzhou, twenty hours of CCTV across three airports, everyone knowing his real name. And for what? I accept the Q Suites are exceptional-I never thought in my lifetime I’d be able to shut a door on a long-haul flight. But still. The risk seemed wildly disproportionate to the reward.

The greatest puzzle solver of all admonished me from another age...

“When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth.”

The improbable that remained was almost indistinguishable from the impossible.

Behold my 3 improbable answers, as nothing else seemed to fit:

Alaska is unable to install basic cyber defences, let alone 2FA, because their tech is from the middle ages.

You don’t need cutting edge threat vector management software to stop these thefts. You don’t even need 2FA. You just need to add a hurdle to stop last minute premium one way flights in another person’s name in geographies far away. Or make you click your email to confirm. Or pick another rudimentary idea. Sure 2FA if for when suspicions are stoked. But without doubt, the reason none of these things are happening, is because their tech stack is too complex, or too brittle, to do any of these things

The penalty imposed on the victim may not be condign

The eleven victims who came forward in the thread suggest this is far from an uncommon problem. Yet people are praising Alaska as though they were showing regal munificence. Consider the PIN requirement. It is baffling, as the previous password is extinct. So by removing the victim’s ability to book their flights freely online henceforth, there is a clear undercurrent that the victim cannot be trusted anymore.

Mr. Xie may not be the devil-may-care risk taker he seems at first glance.

Mr. Xie has 11 implied kindred spirits from this thread alone. system. Why there must be enough of Mr. Xie’s myrmidons to merit a convoluted telephone verbal PIN. All embarking on hellraising risk for a rather ephemeral reward. . A sitting duck from when you book (for fear of interception at the airport like Mr. Xie), to when you leave the ports at your far-flung destination.

Which tells us the odds of avoiding detention must be much better than would imagine. Yet the singular action Alaska Airlines could take to extinguish this threat, no matter their Elizabethan technology stack, is to relentlessly get the Xie-Train detained, and use their marketing machine to plaster the apprehension all over Guangzhou. Demand would evaporate and the hackers would move on to more fertile targets.

It seemed to me everyone in that LinkedIn thread had everything upside down. They were praising Alaska’s customer service, but on closer examination, the praise seemed to obscure these mysteries.

I’d like to say the game was then afoot.

But I could have been wrong. I know nothing about any of these topics. That is the problem with armchair sleuthing I suppose. But I did casually look into it then. Then got distracted by something else. Repeated that motion a couple of times.

Seeing the Seattle Times detailing that nothing had changed since August, made Mr. Xie trouble me once more. I was inspired to share the above with the world, and my investigation below.

Act 2: The Scale of Mr. Xie and Friends’ Travels

As someone who formerly ran a web-scraping company, I’d like to say I dusted off my scraping gloves for old times sake, but greater folks than I handled that, But I did hone copy-pasting skills in my earlier corporate career, which I used to compile as many hacks as I could find up to the end of November this year.

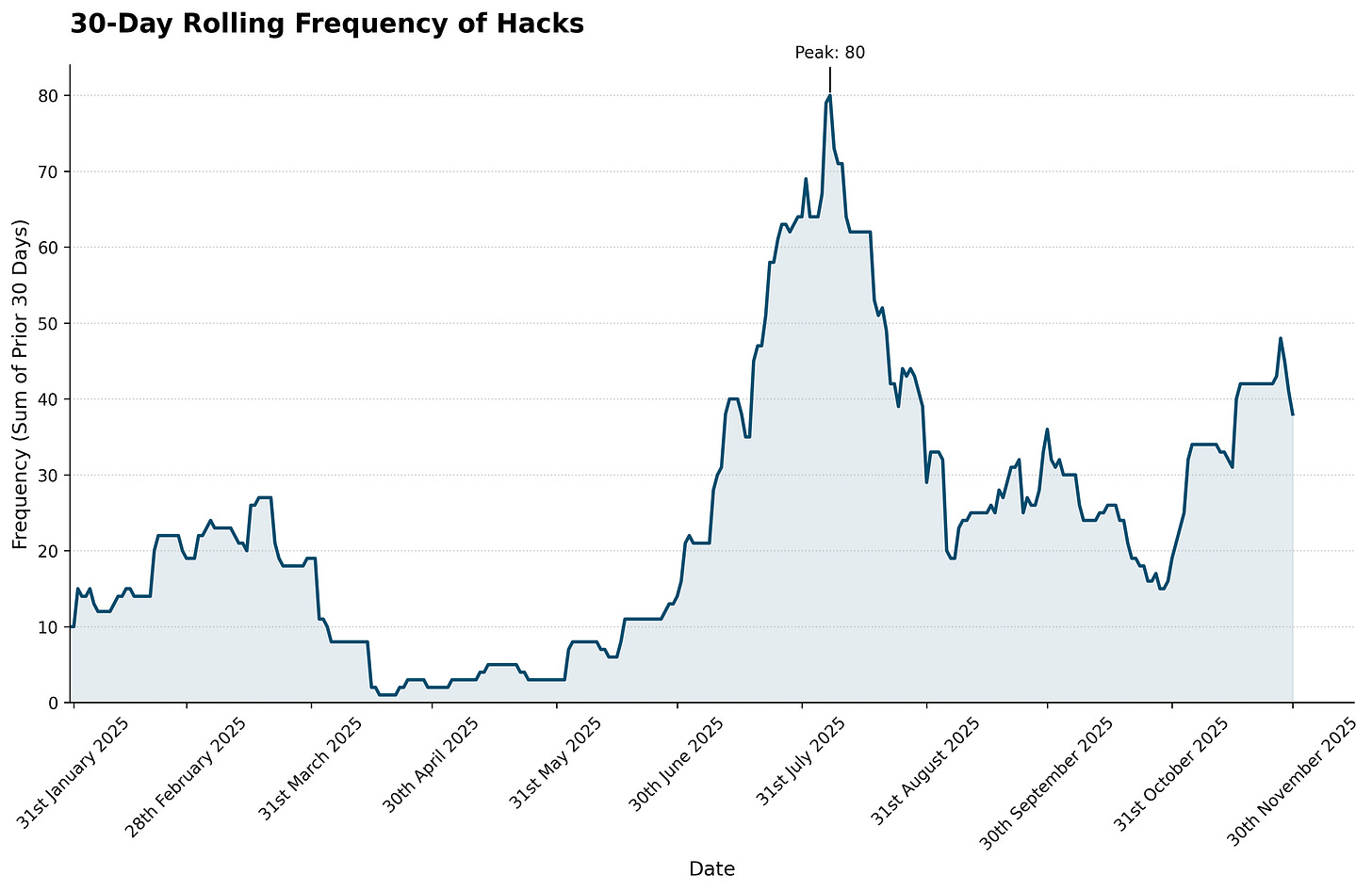

A not insignificant 265 hacks in 2025, 140 of which were in Q3, and 39 were in November.

You can see them all for yourself here.

Just under half were found on Reddit, with Facebook groups providing the next biggest source at around a fifth.

The details were almost uniform. A member discovers an unknown long-haul premium cabin flight booked on their account with a partner airline. No notification was received. This was sometimes before, sometimes during, but largely after the flight had taken place.

Of the 80 victims who numbered their ordeal, losses averaged 218,000 miles.

Alaska’s customer service team’s response was as regular as a metronome

Send some further Personal Identifiable Information (PII) as ID over (unencrypted) email

Upon receipt, miles were restored.

The victim is warned Alaska will only do this once as a courtesy.

The actual combination appears to be to call, then announce verbally a PIN, which briefly restored your online privileges for an hour.

The Reddit threads have a very familiar pattern.

Exhortations for people to ‘stop re-using the same password!’

Less common, but few threads go without a little abuse for the victim: “you had a crazy simple basic password that was easy to guess or reset. I’m sick of taking the slack for people who aren’t careful online.” from this charmer (archive)

A chorus of praise again for Alaska’s redoubtable customer service and their trust and rapid replenishment.

A wave of 2FA campaigners. who remain baffled by its absence.

A litany of lurkers inspired to come out of the woodwork and say ‘me too...’. The 114 hacks

Yet how troublesome this looks for Alaska rather depends on how they fare against other major US airlines.

What we can say with confidence is there’s a familiar, repeatable hack happening to Alaska’s high-value card members, and the hacking is happening at a much greater frequency than it was earlier in the year

Act 3: Comparative Damnation

Worldly readers may be chortling at my naiveté: “Yes, it happens to everyone. That is travel these days. The way of the world alas!” Many of you may have read stories of it happening to many different airlines and many different hotels.

But I challenge you to go and do a search right now, ruling out over as a specified date after the 1st of January 2025, for miles stolen or miles hacked .In the USA, it’s Alaska first and the rest nowhere.

However I shall attempt some quasi-scientific rigour to show this.

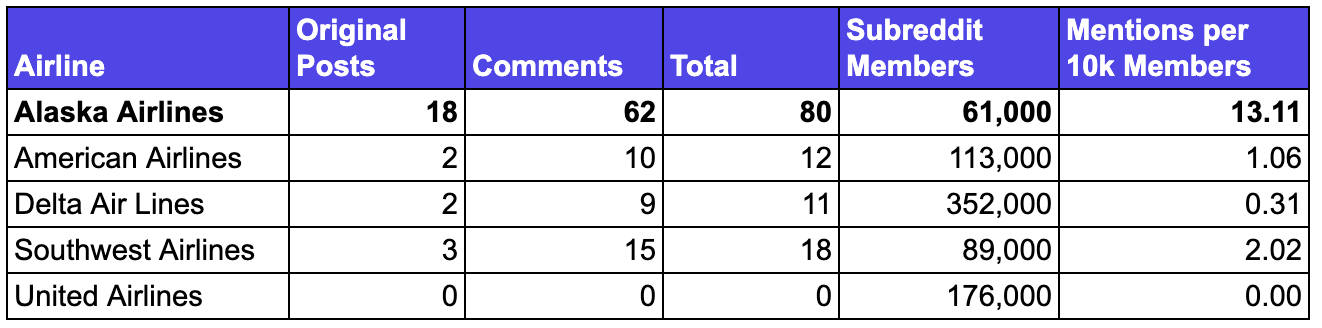

I isolated my search to Reddit as it was the most frequently cited channel. Also because it’s open to Boolean search within each airline’s subreddit. I looked for posts with “hacked” or “stolen” in the title and text. After eliminating those relating to stolen suitcases and travel hacks, I read the comments to see who else announced their account being compromised. I time-boxed the analysis for this year up to the end of November.

So with each airline, it looks after the first of January up to the 31st of November for threads that contain the words “hacked” or threads that contain the words “stolen.” I then,

The results:

Alaska’s normalised reporting rate jumps out. With the smallest subreddit of the five, Alaska has more reported hacks than all the rest combined.

This was certainly an industry-wide problem. Three of those four airlines have implemented 2FA, and Southwest must have more robust security defences without having 2FA.

Alaska appears to have become disproportionately targeted, potentially because it represents the path of least resistance among major US carriers.

The data suggests not only that the hacking of Alaska is not isolated and the frequency at Alaska has increased, but that Alaska appears to be materially more vulnerable than the other major airlines.

Act 4: The Scale Question

The hacks presented a further puzzle. Not because the number is particularly large compared to Alaska’s 12 million loyalty members, but because of what it implies about the total scale.

We know the numerator: 265 reported cases. What we don’t know is the denominator: how many total hacks actually occurred?

Why Most Victims Never Post

Consider what must happen for a victim to appear in my dataset.

Not many people post online. Of those who do, only a fraction use Reddit (where 44% of our reports came from), specialised Facebook travel groups, or my fave, the US Card Forum.

But more importantly, invariably the victims had their miles back. There was no motive for restitution in posting. The crisis was resolved. Why bother?

We must also consider that posters invariably received a little opprobrium, not sympathy, for being hacked. Reddit threads reliably produce lectures about password hygiene and accusations of negligence.

I’d also add the story is rather humdrum. The sort you tell to your partner when you come home, or your dog, and you see, even in their patient eyes, that you having lost some miles and got them back again is not commanding the sympathy or interest you hoped for.

All of this suggests the reporting rate is likely to be low.

The US Card Forum Proof Point

The case of the US Card Forum is particularly instructive. You may not have heard of it. It is in Chinese and caters to US residents who presumably speak Chinese looking to make the most of credit card rewards. It is not focused on frequent flyers. Its About page boasts of 12,000 unique visitors the previous week. It has attracted over its 5 year life, 30,000 registered users in total.

Yet 33 separate individuals reported Mileage Plan theft on this single platform in 2025.

Pause on that for a moment. Thirty-three reports from a community of 12,000 weekly visitors on a non-aviation website. If this were an isolated problem affecting a handful of accounts, we would not see this concentration of reports in such a niche forum.

The US Card Forum datapoint alone suggests the 265 cases I found represent a fraction of the true scale.

Some Clues From the Helpdesk

Victims recounted a little insight from when they reported their loss:

“The CSR said that unfortunately she has to do this [deal with a hacked account victim] 3-5 times per day and if the flight has already flown then miles are gone.” #10053 (archive)

“...one of the agents told me that ever since they launched the new Atmos rewards program they have been seeing a lot of fraud.” #10186 (archive)

“Customer Care admitted they were aware of this ongoing security issue yet there was no urgency in addressing it.” #10007 (archive)

If one rep is handling three to five cases a day, the mathematics starts to look rather different.

You Pick Your Number

So let us run the numbers for Q3, where we documented 140 hacks.

If 5% of victims post publicly, that implies 2,800 total hacks in Q3 alone. If these hacks continued at the same rate as Q3 for a year, we can multiply these numbers by four: over 11,000 annual hacks.

If 2% of victims post publicly, that implies 7,000 hacks in Q3. Annualised: nearly 28,000 hacks.

If 1% of victims post publicly, that implies 14,000 hacks in Q3. Annualised: nearly 56,000 hacks.

I genuinely do not know which figure is correct. I couldn’t find any research that was a worthwhile parallel. But putting it all together, it is hard to imagine that even 5% of victims took to these forums to grumble about their misfortune.

Go on - pick your number from what we have learned.

Whatever number you choose, we are not talking 265 victims. Divide 265 by your yardstick.. and that is the YTD victims. Take Q3’s avalanche and do the same, then times it by four and you get a large number for an annualised rate.

Without doubt we are in the thousands, with a high balance a prerequisite for being robbed may have been compromised and subsequently subjected to account restrictions. This raises questions about whether the burden of security failures is being appropriately allocated between the company and its members.

I’ve gone with 1% by the way. With a very wide margin of error. Honestly it’s just a boring story. That US Card Forum was the clincher.

Act 5: The Human Cost

The 265 documented cases are not merely statistics. The comments reveal a pattern of frustration stemming not only from the hacks themselves but from Alaska’s response: the lack of preventative security measures and the punitive solutions imposed on victims.

The PIN Penalty

The standard procedure after a hack is to lock the account with a PIN, requiring victims to telephone customer service-often for 45 minutes or more-to unlock it for an hour to book award travel. The department works office hours Monday to Saturday. Anyone who has tried to book a long-haul flight with their miles knows it is a complete fiddle. Tarrying over a good deal is costly. Tarrying now means waiting until the office opens and getting through on the phone then logging back on to see if your flight is still there...

For frequent travellers, this is unworkable:

“Problem is I buy flights weekly and sometimes there is a 45+ minute wait on hold. And its not their 24/7 reservation team that can do it, it’s the tech team that closes at night so lots of times I was stuck unable to buy flights at all when I wanted to.” #10003 (archive)

Multiple users reported missing award availability entirely. By the time they reached customer service to unlock their accounts, the tickets were gone.

“The worst part is they make you put a pin on your account YOU HAVE TO CALL TO REMOVE. You sit on hold for hours just to use miles. You won’t be able to book with miles outside of business hours.” #10182 (archive)

The One-Time Courtesy

When miles are reinstated, victims are typically told it is a “one-time courtesy” and warned that if they are hacked again-especially if they opt out of the PIN process-they will not be reimbursed.

“My account gets hacked and 55k miles are stolen. I am given two options: 1. Call EVERY SINGLE TIME I need to use my points OR 2. Book online but if miles are stolen @AlaskaAir WON’T recover those points.. @AlaskaAir How does that make sense?!” #10213 (archive)

“They warned me that they would not assist me again in recovering stolen miles if my information is somehow stolen again (which... they didn’t help me in the first place! I got everything back myself. If anything me supplying the data point was helping them).” #10142 (archive)

Most remarkably:

“We got all the miles back and were told ‘if we find out this was you. We will peruse[sic] prosecution’.” #10011 (archive)

The apportionment of blame from the CSRs appears to be visceral at times.

The Service Experience

Whilst many praised Alaska’s customer service for swift mile restoration, the experience of actually getting through to someone was frequently nightmarish. Wait times of two to three hours were common.

“Customer service is the worst. [...] Tried to call Alaska (in the pm) for a booking yesterday I had to wait on the phone for 2.5 hours (no option for a call back). Spoke to three of the rudest CS reps I’ve ever spoken to in my life (they all seem to think they are better than you).” #10022 (archive)

“130,000 rewards points stolen [...] Impossible to get an answer or assistance from Alaska/Atmos. Best thing I’ve gotten is an auto reply from customer service saying they will get back to me in 3 weeks...” #10216 (archive)

Of course this is a hopelessly unscientific figure because nobody moans about a short hold time. But the 37 that did moan about a hold time had a mean of over a 100 minutes waiting.

The Unreimbursed Costs

Of course, when you book a reward flight, you often have to pay money as well-taxes, fees, surcharges. If you were unfortunate enough to have your credit card associated with your account, that may have been the card that was charged for the fraudulent booking.

Yet Alaska does not see that as their responsibility. They refer customers to their credit card company to seek redress:

“I got hacked luckily they caught it and froze my account and gave me back my miles but had to go to my CC company to get the refund on the on file.” #10026 (archive)

This creates an additional step for victims. If the credit card company accepts the chargeback, it would typically seek recovery from Alaska. The net effect of referring customers to their card issuers is to add friction to the reimbursement process.

The victim accounts suggest the underlying cause of these incidents may be architectural vulnerabilities rather than individual user negligence. If that is the case, referring customers to their banks to resolve charges that resulted from system compromises raises questions about appropriate responsibility allocation.

The Indignity of It All

What emerges from these accounts is not merely inconvenience but a sense of indignity. These are customers who have been loyal to Alaska, often for years. They have flown the airline. They have used the co-branded credit card. They have accumulated substantial mile balances.

Then their accounts were compromised, their miles were stolen, and the response pattern involved proving their identity via unencrypted email, receiving warnings that restoration was a one-time courtesy, and accepting permanent restrictions on their booking capabilities.

If Alaska is getting penetrated at 24x the rate of the other airlines, either Alaska members are 24x more slapdash with their passwords, or Alaska is 24x more slapdash with its cybersecurity.

For customers who may have done nothing wrong, this sequence represents a significant degradation of the programme value they had accumulated, whilst the underlying vulnerabilities enabling the compromises have not been publicly addressed.

Act 6: The Unapprehended Traveller Paradox

The most inexplicable element of this entire investigation at the outset was Mr. Xie.

Actually, not just Mr. Xie. But Team Xie - the thousands of his fraternity availing themselves of these fraudulent tickets

Mr. Bhuiyan caught OG Mr. Xie before the flight even departed. The miles were restored within 40 minutes. Alaska had the passenger name. The itinerary. The booking confirmation. The departure time. Everything needed to notify law enforcement or Qatar Airways.

56 victims in our docket caught the fraud before the flight departed. Alaska was alerted in time to stop the traveller. In several cases, victims reported that Alaska confirmed they had “flagged” the fraudulent booking.

I have searched for any record of arrests, detentions, or refusals of boarding related to Alaska Airlines mileage fraud. News databases. Court records. TSA security incident reports. Border enforcement actions. Let’s not pretend I didn’t give up quite quickly, but I didn’t find anything.

Every fraudulent booking requires a real person to present themselves at an airport, show identification, pass through security, and board an aircraft. These travellers are using their real names on the reservations.

A few high-profile arrests would likely collapse the market for stolen miles. If travellers believed that using stolen miles carried a meaningful probability of detention, demand would contract significantly.

The reasons for the absence of publicly documented enforcement action are unclear. The persistence of the market suggests that those purchasing fraudulent tickets perceive the risk of consequences as low, though whether this perception is accurate, and what factors have shaped it, cannot be determined from public information.

How can that possibly be?

Act 7: The Technical House of Cards

The prevailing narrative attributes these breaches to individual user negligence: weak passwords, phishing emails, the usual litany of digital carelessness.

This premise is difficult to reconcile with the documented evidence.

Alaska’s infrastructure lacks security controls that have become standard practice across comparable industries. The pattern of documented breaches raises questions about whether systemic vulnerabilities, rather than 265 separate instances of user negligence, may be the primary factor.

The Missing Defences

No Multi-Factor Authentication

Alaska does not offer 2FA. Not as an option. Not at all. In 2025, this places Alaska in rarefied company alongside precisely no other major US airline.

The absence is notable given industry trends. Implementing 2FA is a well-established practice; banks, email providers, and social media platforms adopted it years ago. The continued absence at Alaska, despite eleven months of documented incidents, raises questions about whether technical constraints or other factors have prevented implementation.

Silent Credential Changes

When someone changes the email address or phone number on your Alaska account, the system does not alert you. Not a text. Not an email to the old address. Nothing.

This feature makes unauthorised access trivial to conceal. One victim (#10177 archive) discovered the breach only when they tried to log in and found their credentials no longer worked. Another (#10144 archive) learned about it from a third-party mileage tracking app, not from Alaska.

Those exploiting these vulnerabilities appear to have a detailed understanding of how Alaska’s systems operate.

A Fossilised Website

A cursory browse of Alaska’s website reveals it is co-hosted by what appears to be a now-defunct translation third party (archive). The Spanish-language version features charming error pages (archive) that inspire little confidence in the underlying infrastructure.

One gets the impression that touching any part of this architecture risks the digital equivalent of a Victorian ceiling collapse.

Direct Evidence of Non-Credential Access

The “weak password” narrative would be more convincing if the breaches required passwords at all.

In July 2024, a user posted on Hacker News (archive) describing an incident where logging into their Alaska account randomly granted them access to other customers’ accounts. Complete access: names, record locators, flight information, phone numbers, email addresses, and the ability to cancel or modify their flights.

When they refreshed the page, they got a different customer. Trevor, flying JFK to Seattle, then back to Newark.

They reported the vulnerability to Alaska. The response: 3,000 miles (worth approximately $30) and a request to log out and back in. The issue appeared to be resolved.

Four months later, the user reported the same issue occurring again. This time the user saw different passengers’ details. Same apparent vulnerability.

The user posted: “I figured Alaska had done absolutely nothing to fix the issue.”

If accurate, this describes a vulnerability unrelated to credential stuffing or phishing: an architectural issue that permits session access independent of authentication credentials.

The Accidental Tourists

Numerous other users report accidentally accessing others’ itineraries or receiving strangers’ emails. Here’s a small sample from Reddit alone:

These are not hackers. These are random customers stumbling into data they should never see, discovering that Alaska’s systems cannot reliably distinguish one user session from another.

If ordinary passengers are accidentally wandering into strangers’ accounts, what are competent hackers doing?

When Strong Passwords Don’t Matter

The credential-based explanation collapses entirely when confronted with victims who demonstrably did everything right.

Several victims explicitly stated they used unique, strong passwords generated by password managers (#10064 archive; #10085 archive). One was a database security professional (#10022 archive)- precisely the sort of person who would notice poor security hygiene in their own practices.

Then there’s the victim whose account was hacked twice in one day, with a password change between incidents:

“Hacked atmos account, TWICE in one day, even after changing password. How does that even happen?? Couldn’t get through to customer care, it was a 3+ hour hold time. Tried again this evening when I found the second hack and another person flying on my miles... 30 minutes and waiting.” #10228 archive,

The only explanations are either (a) the hacker retained session access independent of credentials, or (b) the hacker had direct database access and the password was irrelevant.

Neither scenario involves user error.

The PIN Paradox

Most damning of all: at least two users (#10061 archive, #10209 archive) report being hacked despite having Alaska’s mandatory PIN lock already in place,

The PIN system is Alaska’s prescribed remedy. After a hack, victims are told they must use a PIN and telephone authentication for all future award bookings. This supposedly adds security.

Yet these accounts were compromised anyway. The attack bypassed both the user’s password and Alaska’s own secondary protection.

One victim (#10094 archive) reported tickets being booked in their own name - as though the hacker had matched the account details with the intended traveller. This implies access to information far beyond what password theft provides.

The Statistical Improbability

Even if we generously assume every documented case resulted from credential compromise, the mathematics don’t work.

If the conservative estimate of 12,240 annual hacks is accurate, and assuming (hypothetically) that only 2% of Alaska accounts hold sufficient balances (200,000+ miles) to be worth targeting, hackers would need to access over 600,000 accounts annually to yield the required number of high-value targets.

That’s more than one account per minute, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. For an entire year. Without Alaska noticing.

Credential stuffing operates through automated attempts across many platforms, trying leaked passwords. It does not efficiently locate specific high-value accounts within a single platform. The precision targeting observed - almost exclusively wealthy accounts with substantial mile balances - suggests either direct database access or a fundamental application vulnerability that allows targeted account enumeration.

The scale is incompatible with the “weak password” narrative.

What This Adds Up To

Alaska’s infrastructure exhibits multiple, documented vulnerabilities:

Random session access granting view and modification rights to strangers’ accounts

Data segregation failures causing customers to receive others’ emails and see others’ bookings

Silent credential changes with no notification to the legitimate account holder

Absence of basic security controls (MFA) standard across the industry

Compromises that bypass even Alaska’s own PIN protection

Precision targeting inconsistent with automated credential attacks

The documented patterns are difficult to explain through 265 separate instances of user negligence. The evidence is more consistent with architectural vulnerabilities that permit unauthorised access independent of individual password practices.

The emphasis on user credential hygiene in public discussions may have the effect of directing attention away from questions about system-level security controls.

Act 8: What About The Money?

All this talk of hacks and victims and Mr. Xie’s travels is rather abstract. Let us make it concrete. What might this actually be costing?

We have two known quantities. First, the 265 documented hacks, with an average theft of 218,000 miles. Second, the knowledge that these 265 appear to represent some fraction of the true total, a fraction we have spent considerable effort estimating.

What we need now is a price per mile.

When Alaska pays Qatar Airways to transport Mr. Xie in his flatbed, they don’t pay in miles. They pay in dollars. The precise amount is commercially confidential and I have found no reliable public insight.

Thus I shall use 0.75 cents per mile as my working estimate for illustrative purposes.

I initially belaboured this - but far quicker to combine 218k miles, at 0.75c a mile, and 26,500 victims and have approximately $43M. Because the calculation infers a science which that number does not have. Put in your own inputs and you can get your cost estimate.

If you are anywhere near me on this estimate, that is not a small amount. ALK made $395M in Net Income. Materiality for disclosure starts normally at 5% of profits - so $20M and ALK are broadly (not a fast rule) obliged to tell their investors about this problem.

Which raises an obvious question: if the losses were material, where would they be in the accounts?

Act 9: The Silent Victims

We have focused thus far on the visible victims: those who discovered their miles had vanished and took to the internet to complain. But there is a larger population we have not yet considered.

Consider what the hackers must do to find a Mr. Bhuiyan.

They cannot simply guess which accounts contain 200,000 miles. They must look. They must access accounts, check balances, and move on when the cupboard is bare. The accounts worth plundering are a small fraction of the total. Most Mileage Plan members have modest balances, a few thousand miles from occasional flights, nothing worth the effort of arranging Mr. Xie’s itinerary.

I have at least half a dozen accounts with miles received but never used that alliance again with accounts scattered across various airlines. I could not tell you the passwords to most of them. Only one contains anything of value. The others hold the residue of long-forgotten trips, balances too small to redeem for anything useful.

Members with 200,000 miles are not typical. They are the heavy spenders, the road warriors, the credit card optimisers.

So let us work backwards.

If my central estimate of 26,500 successful thefts this year is correct, and if accounts worth stealing represent just 2 per cent of the membership, how many accounts must the hackers have accessed to find their targets?

Why 1.3 million accounts.

To be honest, data breaches seem so commonplace - I think my DNA got snaffled in 23andMe so not much left after that. But I don’t have children. For family accounts, the names and birth dates of children are likely all within

This is identity theft substrate of the highest order

But I wonder if I am looking at this the wrong way round in estimating the scale of breaches.

I would not care how many people told me buying these flights out the back of a lorry was safe as houses, I’d not be tempted.

Perhaps the limiting factor is demand, not supply. Mr. Xie can only go on so many jaunts a year.

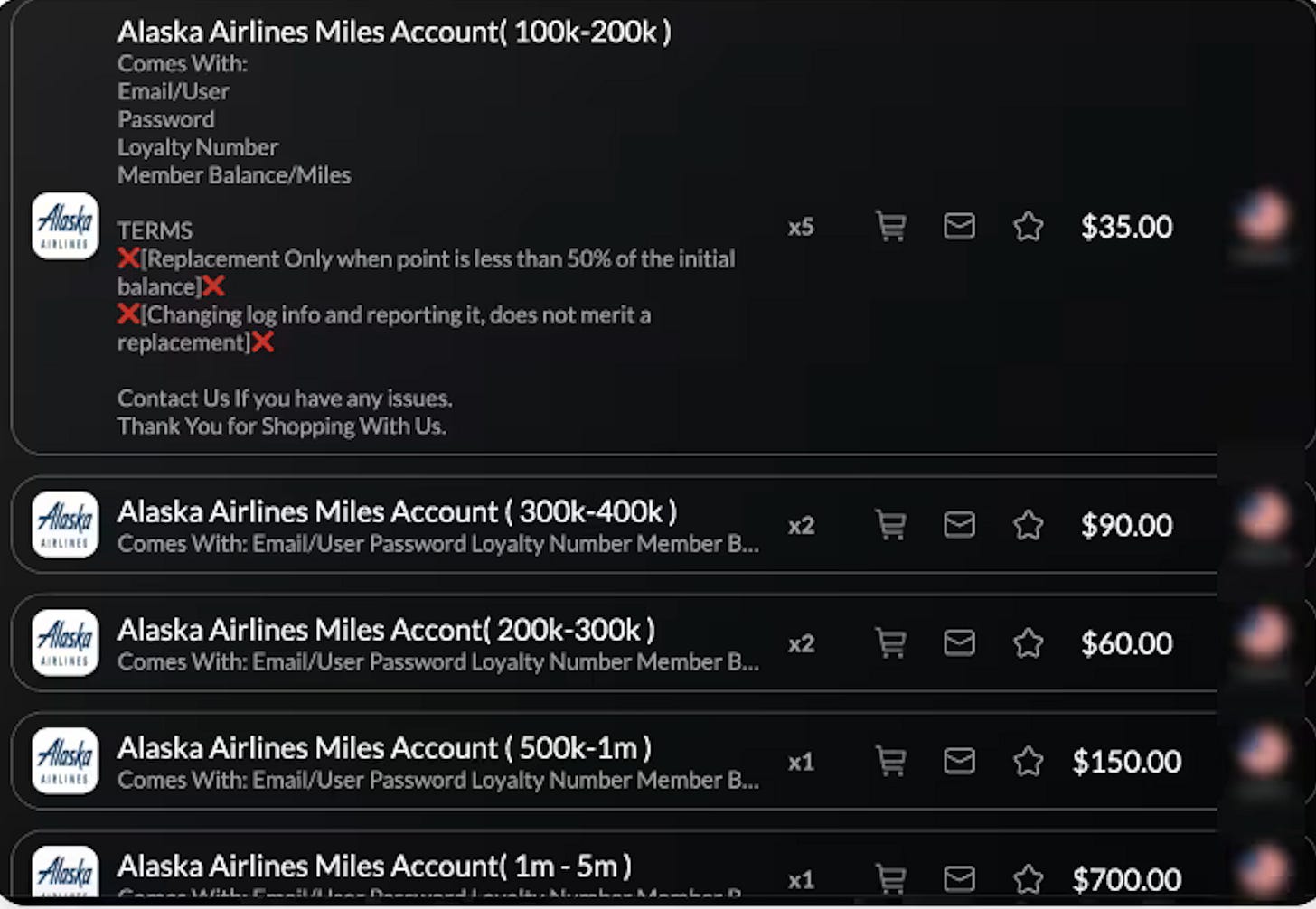

As look at the prices on the dark web (archive)!

The Xie Man put down 35 sheets to get a bed, a duvet and a door from Guangzhou to London.

The terms of sale are equally revealing. “Replacement Only when point is less than 50% of the initial balance.” In other words, if you buy an account advertised as holding 300,000 miles and it turns out to contain only 140,000, you get a replacement. The seller guarantees their inventory.

Act 10: The Summer of Hacks

There is a pattern in the data I have not yet mentioned.

The 265 documented hacks are not evenly distributed across the year. They cluster. And the clustering is suspicious.

A word of caution before we proceed. My dates are reporting dates, not incident dates. When someone posts on Reddit that their miles have been stolen, others often reply “me too” in the comments. I record those on the same day, but the underlying incidents may have occurred over weeks. I have counted hacks regardless of when the poster announced it was. Because if you rule out those in the past, you’ll never catch them in the future. Today’s hacked may mention it next year.

So ignore the daily noise. Look instead at the trend.

When I smooth the data to a 30-day moving average, a clear pattern emerges. The baseline from January through May hovers around 0.4 reports per day. Then something changes.

From late June through August, the average more than triples. It peaks in mid-July at nearly 2 reports per day. It subsides somewhat in September and October, then surges again in late October and November. As I write this in early December, the trend is climbing again.

Now look at this, from Alaska’s 8-K filing (archive) dated 27 June 2025:

“On June 23, 2025, Hawaiian Airlines, an Alaska Air Group, Inc. subsidiary, identified a cybersecurity incident affecting certain information technology systems.”

The Hawaiian Airlines cybersecurity incident was disclosed on 27 June. The 30-day moving average of documented Mileage Plan incidents began rising shortly thereafter. By mid-July, it had approximately quadrupled from the spring baseline.

I must be careful about causation. Summer is peak travel season. More people checking accounts means more discoveries. Bon vivant’s like the Xie-Team prefer the summer months to globetrot no doubt. But the timing is striking.

Alaska’s Q3 10-Q (archive), filed in November, concluded:

“Based on information currently available, we do not believe the incident had, or is expected to have, a material impact on Hawaiian’s business, results of operations, or financial condition.”

Which is a curious statement. One would expect upon breaching the cyber defences of a target, no doubt a moment in which they allow themselves a brief moment to rejoice, the hackers have a nefarious objective. If you do not know what they got up to, that is more worrying than if you did.

Act 11: The Quiet Adjustment to the Terms

Looking for where else I may get some insight, I was inspired to check Alaska’s terms on its mileage programme. There was a chance that a flurry of undesired behaviour may cause another 100 pages to be added to the click-wrapped goo behind every company.

Something had changed. Between 11th September and 29 November 2025, Alaska added a new clause to the Atmos Rewards Terms & Conditions. It reads:

“Alaska Airlines may deny, revoke, or adjust Atmos Rewards points, status points, awards, or benefits at any time, including after they have been posted or redeemed, if determined to have been granted in error, including due to system or partner issues, regardless of member fault.”

Regardless of member fault.

That is a stinker of a clause huh? Not only does it give Alaska carte blanche not to reimburse the be-hacked as the system they run is to blame, they even give themselves the option to take back long ago earned or refunded points on a whim.

No other non-cosmetic changes were made to the terms. So it wasn’t a periodic re-fresh. It directly serves to diminish member’s redress, indeed ownership, of their miles.

Consider this happy camper:

“I had Hawaiians mileage acct for a very long time no issues. Since ‘Atmos’ came along I have been hacked twice for 750 thousand miles now to use my points I have to call in (not on Sunday) they will unlock my acct for one hour so I can book flights then they lock it again...” #10205 (archive)

What makes this tale of woe stand out, is it exemplifies exactly what Alaska specifically pledged not to do.

The agreement by the Department of Transport to the merger was very specifically pre-conditioned on a solemn, and thankfully short, agreement that the CEO himself signed in September 2024 vowing Alaska would not:

“...decrease the dollar value, eliminate, reduce, suspend, forfeit, invalidate, impose new limits on access, use, redemption, or validity, or impose new requirements...”

It goes on. But telephone booking and now terms that say points can be revoked on the basis Alaska’s IT is banjaxed. Seems very naughty to me

I caught one more glimpse behind the corporate mask. In October 2025, the VP of the mileage programme (archive) did a Q&A on Reddit. When an avalanche of upvotes accompanied a question on 2FA’s implementation, he confided:

“fraud attempts are getting worse almost daily. It’s something we take very seriously, and it has visibility all the way up to our CEO.”

Well the top brass know of the problem. “Getting worse almost daily” may just have been a mere turn of phrase - but knowing what we know - perhaps it was not.

Act 12: Following the Money

All this talk of hacks and victims and Mr. Xie’s travels is rather abstract. The time has come to dive into SEC filings.

For those not licking their lips at my impending narrative winding through the joys of ASC 606 and loyalty programme accounting... just skip to the end!

For those still reading, you shall have your tenacity rewarded!

A Brief Primer on Loyalty Point Accounting

Before I show you what I found, you need to understand how airline loyalty programmes work as financial instruments. Think of miles as casino chips - made-up currency, but with real liabilities attached.

When Bank of America (Alaska’s credit card partner) sells Alaska’s co-branded credit card, and a customer earns 100,000 miles, Bank of America pays Alaska approximately 1.25 cents per mile - $1,250 total. Alaska then performs what amounts to financial alchemy.

They split that $1,250 into two buckets. The first bucket, typically around 60%, goes to “deferred revenue” - a liability representing Alaska’s obligation to honour those miles when redeemed. This is valued not at Alaska’s cost, but at what those miles would cost if purchased as a ticket. Alaska values this at 0.75 cents per mile - the “Standalone Selling Price” in accounting parlance. So $750 goes onto the balance sheet as a liability.

The remaining $500 goes directly to revenue as “Loyalty Other Revenue”. Alaska has done nothing except issue digital points, yet they recognise profit immediately. It is, as they say, printing money.

When a customer redeems those miles on Alaska’s own aircraft, the marginal cost is often negligible - the seat would have flown empty regardless. Alaska releases the $750 liability, incurs perhaps $100 in actual cost (food, fuel allocation), and pockets the difference. Absolute cash volcano.

But customers also want to escape North America with their miles. So Alaska has partnerships with carriers like Qatar Airways. When a member redeems miles for Qatar’s Q Suites, Qatar wants actual money - likely 0.5 to 1.0 cents per mile depending on cabin class and route.

The accounting becomes more interesting here. Alaska releases the $750 liability (at Standalone Selling Price) through a line called “Loyalty Redemptions - Partner Airlines”. If Qatar charges 0.5 cents per mile (roughly half the standalone selling price), the difference flows through to “Loyalty Other Revenue” as margin. If Qatar charges more than the standalone selling price - as they might for premium long-haul - that excess reduces “Loyalty Other Revenue” instead of appearing as a separate expense line.

This structure matters enormously for understanding what I am about to show you.

Now, here is where fraud creates an accounting puzzle.

When Mr. Xie flies Guangzhou to London in business class on stolen miles, Alaska initially processes it as a normal redemption. Deferred revenue goes down. Partner redemption revenue is recognised. Qatar Airways sends a bill. So far, so standard.

But then the victim discovers the theft. Alaska reinstates the miles. The victim now has their 185,000 miles back. But the original deferred revenue decrease has already been recorded. Qatar Airways still wants paying.

The textbook treatment is to reverse the original redemption entry and recognise a fraud loss expense. The member’s miles are restored by increasing the deferred revenue liability, and Alaska books the cost of Mr. Xie’s flight as an operating expense

What Alaska should record:

Dr. Fraud Loss Expense (P&L) $X

Cr. Deferred Revenue (Liability) $X

This is transparent. It shows up in operating expenses. It affects profit margins. It prompts questions from analysts.

What I Found

I will show you the data momentarily. But let me first explain what made me look in the first place.

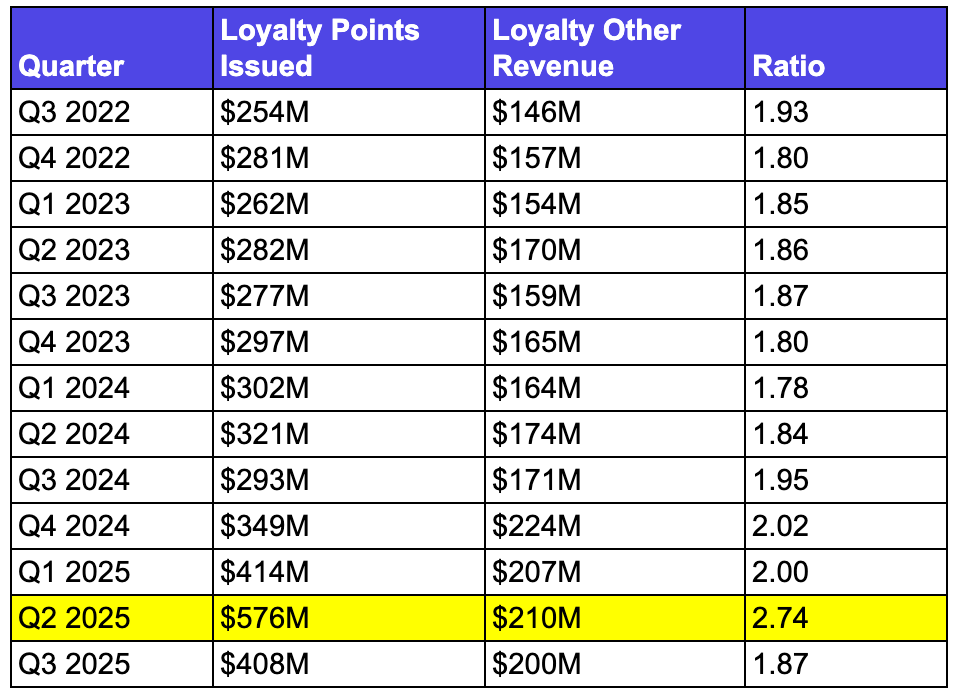

Alaska’s Q2 2025 10-Q, filed in August, contained a deferred revenue rollforward table showing “Increase in liability for loyalty points issued”. This represents miles added to the system - primarily from Bank of America credit card sales, but also from ticketed revenue.

The number for Q2 2025 was $576 million.

Here is what that looks like in context:

Look at that ratio column. For eleven consecutive quarters, it hovers between 1.78 and 2.02, clustering around 1.88. The pattern is stable, predictable, boring in the way airline accounting should be.

Then Q2 2025: 2.74. The ratio spikes sharply, then immediately reverts to 1.87 in Q3.

This is not a trend. This is an event.

The $576 million issuance represents a $180 million excess over what the historical ratio would predict. Alaska created $180 million in additional liabilities whilst recognising almost no corresponding revenue increase.

Yet “Loyalty Other Revenue” - the immediate profit Alaska recognises from mile sales - barely moved. It was $210 million in Q2 2025, $3M higher than Q1 2025, despite the massive spike in issuance.

This is contradictory. If Alaska genuinely sold that many more miles to Bank of America, revenue should have increased proportionally. It did not.

Then I noticed the receivables line. “Receivables from affinity card and other partners” - essentially what Bank of America owes Alaska for miles purchased.

Q1 2025: $111 million

Q2 2025: $306 million

A $195 million increase in a single quarter.

Now, trade receivables from Bank of America settle within 30-45 days. This is not long-term financing. This is ordinary course of business. You would expect that $306 million to convert to cash in Q3.

It did not.

Q3 2025: $177 million

The receivable declined by $129 million. But - and this is crucial - that decline did not generate operating cash flow. I checked the cash flow statement. The reduction in receivables did not produce cash.

Where did it go?

Look at “Other Noncurrent Assets” - the balance sheet’s junk drawer, where tedious items like prepaid maintenance deposits live.

Q2 2025: $316 million

Q3 2025: $436 million

A $120 million increase. Almost exactly matching the $129 million receivables decrease.

The receivable appears to have been reclassified. Moved from current assets (collectible within 12 months) to noncurrent assets (collectible beyond 12 months, or possibly not collectible at all).

This pattern appears precisely once in Alaska’s recent history. Q2 2025. Coinciding with the Q3 hack surge documented earlier.

The Partner Airlines Anomaly

There is another data point that caught my attention. Alaska reports “Loyalty Redemptions - Partner Airlines” as a separate line item - this represents the value of miles redeemed on airlines like Qatar Airways, Emirates, British Airways, and so forth.

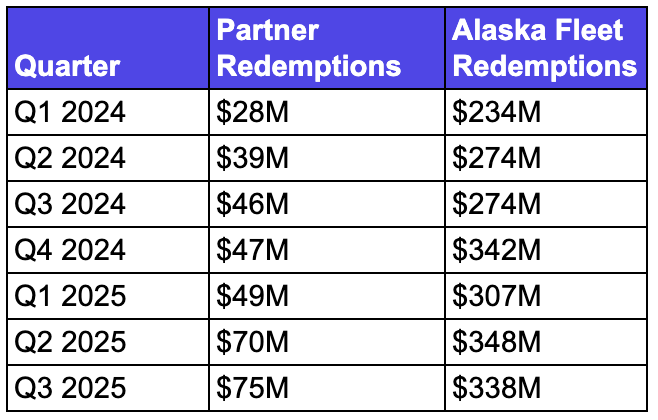

Here is what that looks like:

The baseline runs fairly consistently between $28M and $49M per quarter. Then Q2 2025 jumps to $70M - a $19M increase. Q3 2025 climbs further to $75M - a $26M increase over the historical baseline.

Combined excess: approximately $45M over two quarters.

Now recall what we know about the hack pattern. The thefts target partner airlines overwhelmingly - Qatar Airways features most prominently in victim accounts. Premium long-haul cabins. Last-minute bookings.

When Alaska reinstates miles to victims, those miles return to the liability balance. But Qatar Airways has already transported Mr. Xie to London. They want paying. That payment flows through “Loyalty Redemptions - Partner Airlines”.

The $45M excess in partner redemptions aligns remarkably well with our bottom-up fraud estimate of $43M based on documented incidents and reporting rate assumptions.

Two completely independent approaches - social media documentation extrapolated to total victims, and SEC financial statement analysis - converge on the same figure.

The Retroactive Adjustment

There is one more peculiarity worth noting.

In Q2 2025, Alaska retroactively restated its year-end 2024 affinity card receivables from $118 million to $176 million - a 49% increase. They characterised this $58 million adjustment as “immaterial”.

This is remarkable. A $58 million adjustment to a balance sheet line that previously showed $118 million. The adjustment represents approximately 15% of Alaska’s 2024 net income of $395 million.

SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 99 explicitly warns against characterising misstatements as “immaterial” based solely on quantitative thresholds. Qualitative factors matter: does the adjustment mask a trend? Does it concern a strategic asset? Does it affect compliance with loan covenants?

A $58 million restatement to receivables from Alaska’s largest commercial partner, representing the cash flows that underpin a $12 billion loyalty programme and secure a $2 billion credit facility, would seem to warrant more substantive disclosure than a parenthetical notation of “immaterial adjustments”.

What This Means

I cannot prove what happened. I have access only to public filings, not to Alaska’s internal accounting memoranda or Bank of America contract terms.

But I can describe what the pattern suggests.

It appears that Alaska recorded a substantial volume of loyalty point issuances in Q2 2025 with a corresponding increase in receivables from affinity partners. When that receivable did not convert to cash in Q3, approximately $120 million moved to noncurrent assets rather than flowing through the income statement as an expense or bad debt provision.

One interpretation consistent with this pattern: if miles were issued to restore fraud victims’ accounts, this would create deferred revenue liabilities (the obligation to honour those miles) without corresponding revenue recognition (because no cash was actually received from Bank of America for those particular miles). The receivable spike would represent billing Bank of America for miles that were actually replacements for stolen miles, not genuine new issuances. When Bank of America declined to pay for miles they had not actually sold to customers, the receivable could not be collected.

In simplified terms: if you restore 26 billion miles to fraud victims ($195 million at the implied billing rate), you create $195 million in new liabilities. You then bill Bank of America. They refuse to pay, because their cardholders did not earn those miles - those miles were stolen and reinstated. The receivable sits unpaid. Eventually, you reclassify it from “we will collect this soon” to “this will take some time to resolve”.

The alternative interpretation - that Bank of America legitimately purchased $195 million in additional miles in Q2 2025, generating the unprecedented spike, then refused to pay for them for unrelated commercial reasons - seems less probable.

Expenditures are either expenses (consumption with no future benefit) or investments (acquiring assets of enduring value). If a cost that should reduce current profits is instead recorded as an asset, the effect is to defer its impact on reported earnings.

The Q2-Q3 2025 pattern raises questions about whether such deferral may have occurred. The evidence is circumstantial. Management and auditors may have information supporting a different characterisation. But the pattern was sufficiently anomalous that I spent considerable time attempting to identify alternative explanations from public filings. I was unable to do so.

The accounting anomaly, the cybersecurity crisis, and the financial impact estimates converge. The documented hack count extrapolates to $43 million in direct costs. The excess partner airline redemptions in Q2-Q3 total $45 million. The unexplained balance sheet movements aggregate to $120 million when including the retroactive restatement.

These numbers align very closely.

Act 13: The End of the Trail

This whole investigation has had a discernible outcome. I have taken out a short position on Alaska Air Group stock.

Readers should note my investments are ordinarily 95% in tracker and diversified funds. I own one individual stock. I have bought put options for the first time in my life after this investigation

Indeed I should confess my record on individual stock selection is directly related to why I do not engage in it today - it was decidedly mixed. And I must acknowledge that perhaps because of the direction I came at this investigation, to this hammer, everything looked like a nail.

But three puzzles troubled me back in August when I first encountered Mr. Bhuiyan’s LinkedIn post. I proposed three improbable answers. Time to assess whether my deductions held.

Puzzle One: The Missing Defences

Original question: Why, if this is a common problem, does Alaska not implement 2FA or basic cyber defences?

Improbable answer: Alaska’s technology stack is too complex or too brittle to implement rudimentary security measures.

What we now know: The evidence supports this rather comprehensively. Random session access granting strangers’ account details. Data segregation failures. Silent credential changes. The Spanish-language site co-hosted by an apparently defunct translation service. The Hacker News user randomly accessed other passengers’ accounts - twice, four months apart.

Alaska’s VP of Loyalty confirmed fraud attempts are “getting worse almost daily” and have “visibility all the way up to our CEO”. Yet nine months after that statement, 2FA remains unavailable. The new Atmos platform launched in August did nothing to inhibit the theft rate.

After multiple IT outages that grounded flights, Alaska engaged Accenture on 31 October for a “comprehensive technology audit”. The CFO provided the first public commentary on this engagement just last week, on 4 December 2025, at Goldman Sachs’ Industrials Conference.

His assessment was revealing in what it did not say:

_”we don’t have a systemic architecture failure... Have we just under-resourced ourselves? That’s not what they [Accenture] found.”

He attributed the outages to “hygiene” and “innovation”, noting they had “launched a brand new loyalty platform... and needed to make a lot of updates to our technology, our apps, our website”.

Remarkably, the new platform’s 20 August launch did nothing to inhibit the volume of loyalty points thefts. November 2025 saw 38 documented hacks - the elevated rate continues unabated.

The CFO’s direct response on IT infrastructure represents a de facto statement that compromised accounts are not an issue that has been highlighted. The Accenture audit found no systemic architecture failure. Yet the loyalty platform - the very system experiencing mass account compromises - was cited as requiring “a lot of updates” to underlying technology.

The architecture appears fundamentally compromised. Adding 2FA to a system that randomly grants session access to strangers would be rather like installing a better lock on a door that periodically swings open by itself.

Verdict: The improbable answer appears to have been accurate.

Puzzle Two: The Victim Penalty

Original question: Why force victims into inconvenient telephone-only booking with verbal PINs when the compromised password has been changed?

Improbable answer: The penalty imposed on victims may not be as munificent as the chorus of praise suggested. There is an undercurrent that the victim cannot be trusted.

What we now know: The PIN restriction is demonstrably punitive rather than protective. Victims must telephone during office hours (Monday to Saturday), wait an average of 100 minutes on hold, verbally provide a PIN to unlock their account for one hour, then rush to book award travel before the window closes.

Multiple victims reported missing award availability entirely. One frequent traveller stated the system was “unworkable” for someone who books flights weekly.

Most damningly: at least two users were hacked despite having the PIN protection already in place. The attack bypassed Alaska’s own prescribed remedy.

Then came the terms change. Between 11 September and 29 November 2025, Alaska added a clause permitting them to “deny, revoke, or adjust Atmos Rewards points... including after they have been posted or redeemed... due to system or partner issues, regardless of member fault.”

This directly contradicts the CEO’s signed commitment to the Department of Transportation not to “impose new limits on access, use, redemption, or validity” of Hawaiian Airlines miles as a condition of merger approval.

The victim is indeed being blamed for Alaska’s system failures.

Verdict: The improbable answer was accurate. The praise obscured the reality.

Puzzle Three: The Unapprehended Mr. Xie

Original question: Why does Mr. Xie face so little apparent risk when he is a sitting duck - facial recognition, CCTV, real name, traceable throughout his journey?

Improbable answer: The odds of avoiding detention must be much better than one would imagine. Alaska could extinguish this threat by relentlessly pursuing prosecutions and using their marketing machine to publicise arrests. Demand would evaporate.

What we now know: Of 265 documented cases, 56 victims contacted Alaska before the flights departed. For flights originating in the USA (39% of identified origins), the passenger is on American soil, subject to American law, using stolen property. TSA could have been notified. CBP could have been advised of incoming foreign nationals on fraudulent tickets.

I found no public records of arrests, detentions, or refusals of boarding related to Alaska mileage fraud. The silence is deafening.

The dark web pricing is astonishing. One-way long-haul business class for $35. The terms of sale guarantee replacement if the account balance is less than 50% of advertised - the sellers warranty their inventory.

Mr. Xie faces minimal risk because Alaska does not pursue him. Whether this reflects operational incapacity, strategic choice, or concern about what enforcement action might reveal about the scale of the problem, I cannot determine from public information.

But the market for stolen miles operates openly, brazenly, at prices suggesting vast supply. This would not persist if buyers faced meaningful prosecution risk.

Verdict: The improbable answer was accurate. The risk-reward calculation is not what it appears.

Act 14: The Sleuth Retires

All my sleuthing could be refuted if Alaska disclosed the underlying reasons for the accounting anomaly, explained the $120 million reclassification, and revealed how many member accounts have been compromised.

I highly doubt Alaska management will find their way to my analysis. But the upcoming Q4 2025 and full-year 2025 audit (due February 2026) may prove illuminating. Auditors will have visibility into the composition of “Other Noncurrent Assets”. They will assess whether the $58 million restatement was genuinely immaterial. They will evaluate cybersecurity incident disclosures against the scale of documented breaches.

Regulatory agencies may also develop interest. The Department of Transportation might examine whether telephone-only restrictions violate merger commitments. The SEC might assess whether financial statement presentation complies with disclosure requirements. Washington State’s Attorney General might consider data breach notification obligations.

Or perhaps I am entirely wrong. Perhaps the Q2 spike has a mundane explanation. Perhaps the $120 million reclassification represents something perfectly ordinary that simply was not disclosed. Perhaps 26,500 estimated fraud victims is a wild overstatement, and the true figure is 265.

The time has come for the sleuth to step back and let those who have more than month’s familiarity with loyalty programme accounting and cyber attack vectors to pick up the the mantle.

To formalise whether I am right or wrong, I made a full grown-ups report of my findings here, with a databook to go with it.

I have placed a wager that suggests otherwise. But armchair sleuths, even when armed with SEC filings and ratio analysis, are frequently wrong.

We shall see.