ALK Accounted

BAKED ALASKA ALK 0.00%↑

The $12BN Loyalty Programme Assailed from All Sides

January 2026

A crucial addendum to this report can be found here.

A summary of the entire investigation can be found here.

Download the Full Report.

DISCLAIMER: The author holds a short position in Alaska Air Group (ALK) and stands to profit from a decline in the share price. This report represents analysis of publicly available information, including SEC filings, public financial data, and social media documentation. It constitutes opinion, not investment advice.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Facts (Not Interpretation)

The following facts are taken from Alaska Air Group’s public filings and from a documented dataset of member loyalty point thefts described in the appendices. Each is material. Together, they are extraordinary.

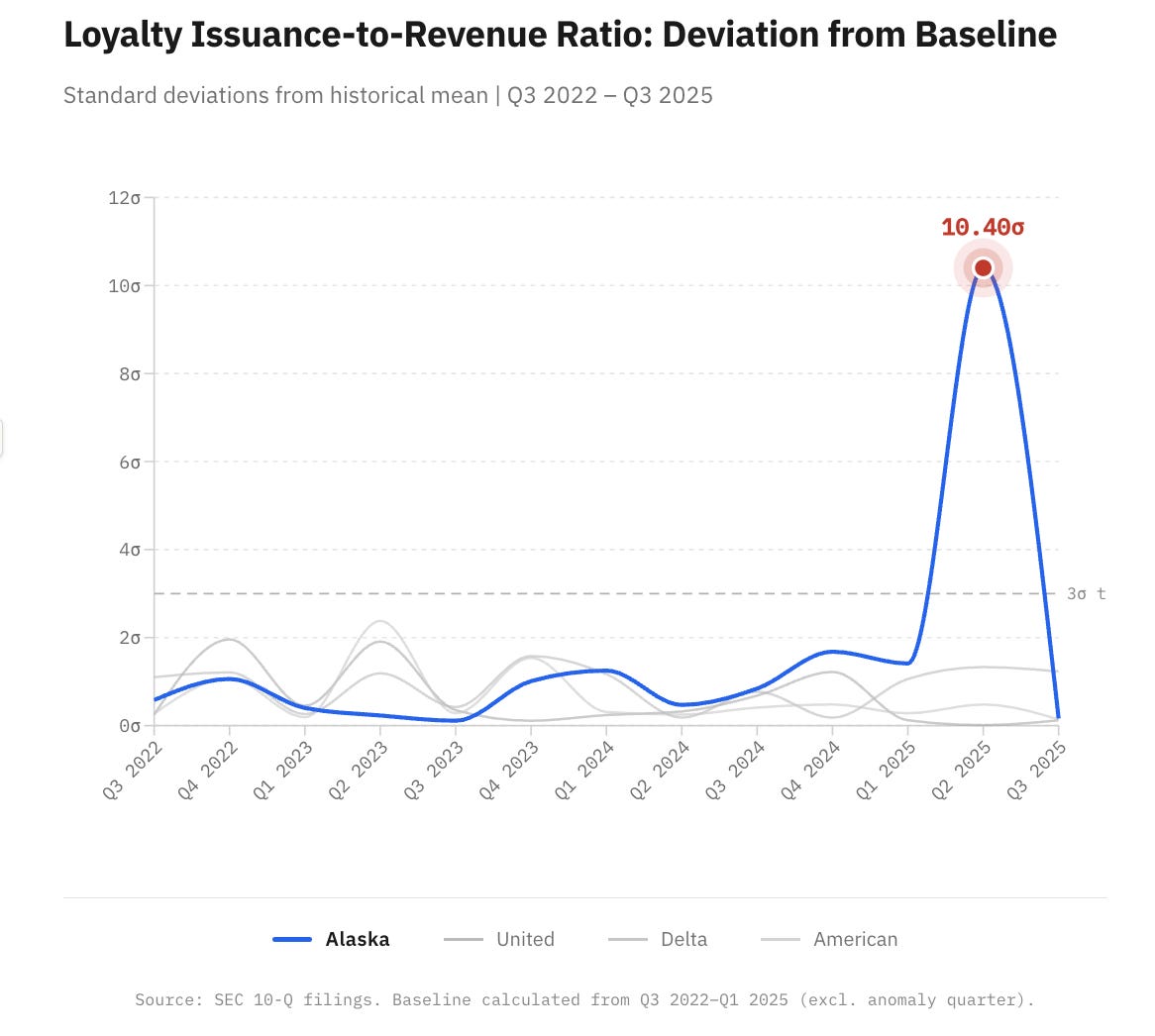

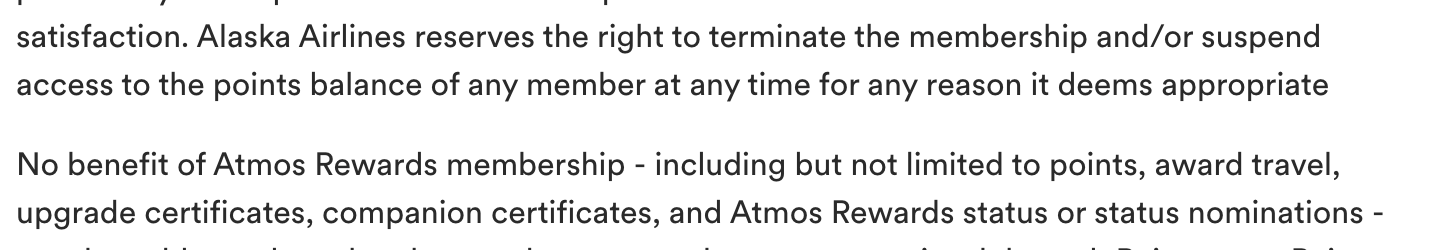

In Q2 2025, Alaska recorded a 10.40σ deviation in its loyalty issuance-to-revenue ratio, an orders of magnitude leap in improbability compared to any other airline in the analysed post-covid period.

The deviation appeared for one quarter and reverted in Q3 2025, indicating a discrete event rather than a regime change.

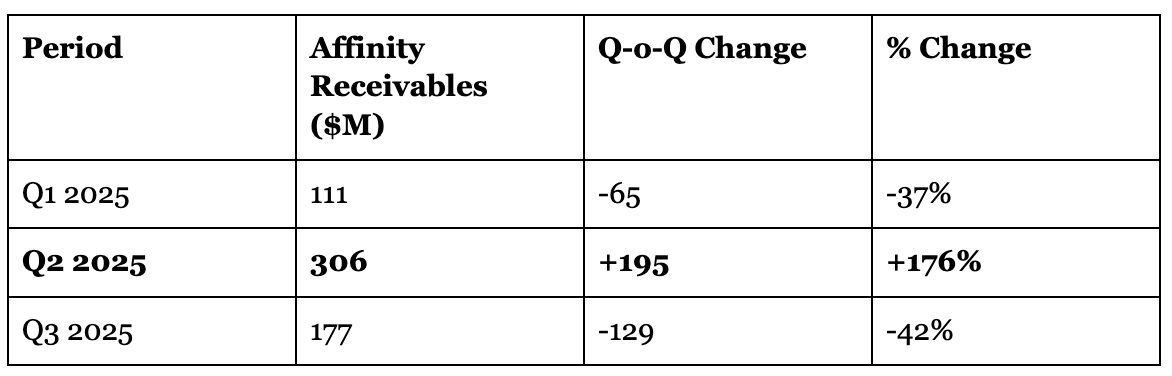

In the same quarter, amounts due from affinity card partners increased by $195M quarter-on-quarter.

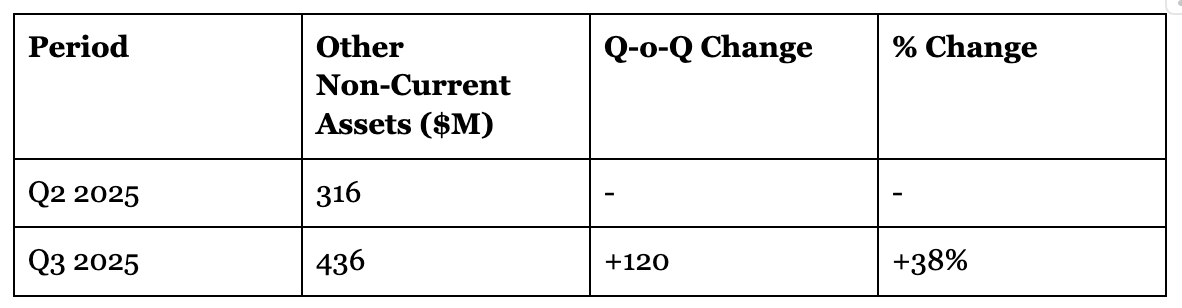

In Q3 2025, “Other Non-Current Assets” increased $120M without disaggregated explanation.

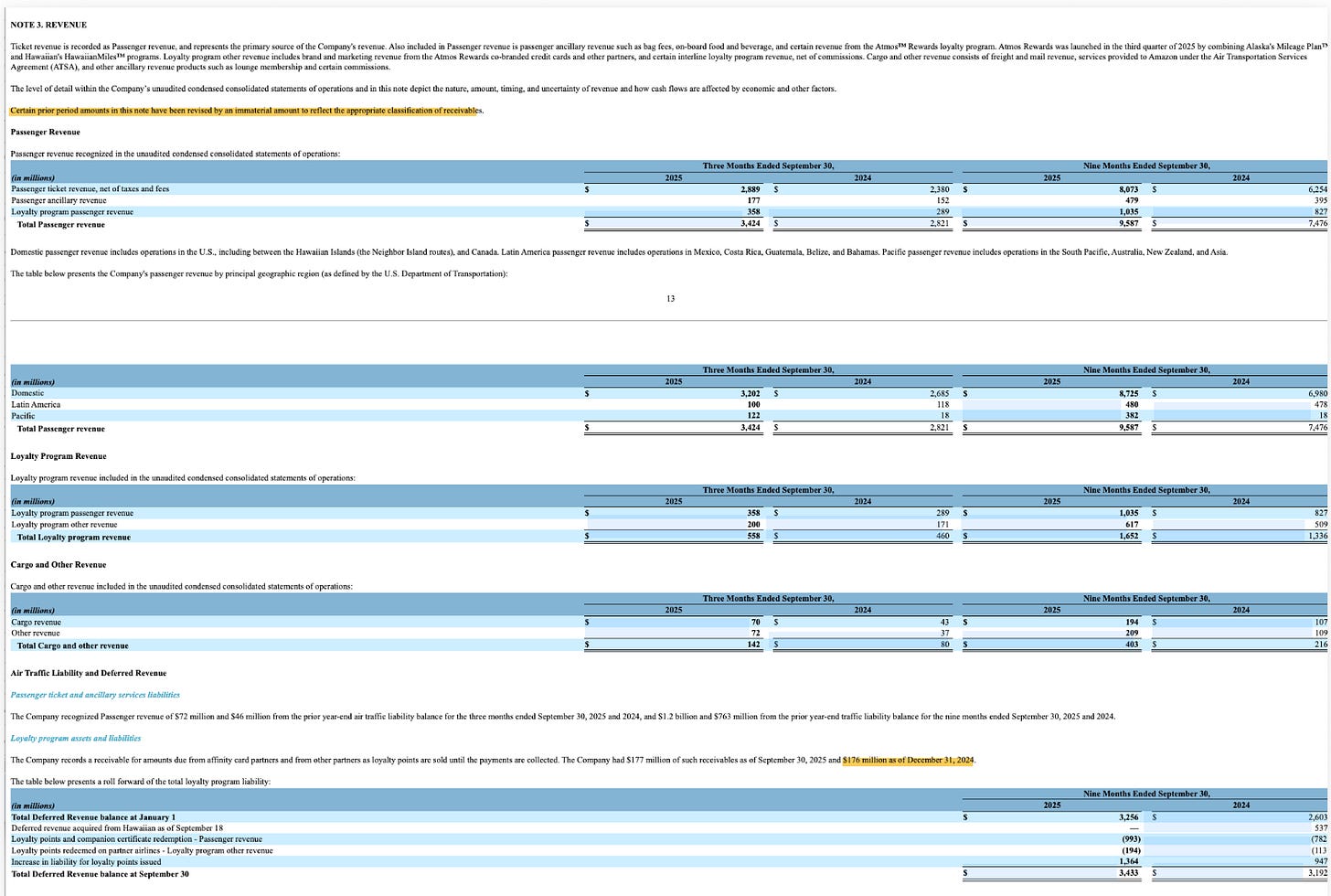

A prior-period retroactive revision increased affinity receivables by $58M (49%), characterised as “immaterial”, and disclosed only after the anomaly quarter.

In 2025, 370 distinct loyalty members revealed points thefts on their accounts.

Alaska’s normalised rate of theft reports is approximately 23.4× peers using the same source and methodology.

On 7 October 2025, Alaska’s Vice President of Loyalty stated:

“We know this is a major pain point, and honestly, fraud attempts are getting worse almost daily. It’s something we take very seriously, and it has visibility all the way up to our CEO.”

These facts are not explained with sufficient specificity to permit reconciliation by investors.

The Accounting Constraint

From the published financial statements, one of the following must be true:

A material change in loyalty accounting judgements occurred and was not adequately explained; or

A material change in affinity partner settlement or collectibility occurred and was not adequately explained; or

A material issuance of loyalty obligations without corresponding consideration occurred and lacks a clearly identifiable offset; or

The reported presentation does not faithfully depict the underlying transaction flows.

There is no fifth option.

Investment Thesis

Individually, the accounting discontinuity, balance sheet movements, and escalating public accounts of loyalty point thefts would each warrant explanation.

Taken together, they raise a more serious possibility: Alaska’s loyalty programme may no longer operate as a closed, fully controlled, auditable system.

Markets do not materially re-rate companies over one-off accounting issues or isolated cybersecurity incidents. They do re-rate companies when confidence in the integrity of a core asset collapses and when management credibility becomes uncertain.

This report contends Alaska Air Group is now at risk of crossing that threshold.

What the Market Should Care About (and What It Should Not)

This report is not about:

regulatory fines

litigation arithmetic

one-time remediation costs

cosmetic reclassifications

Those are linear, modelable risks.

This report is about whether:

loyalty issuance and redemption can be reliably governed

account balances can be trusted as durable economic assets

the platform can be stabilised without wholesale replacement

disclosures fully reflect operational reality

These are non-linear risks. When they crystallise, valuation frameworks break.

The Central Question for Investors

The key question raised by this report is not:

How much will this cost?

It is:

Can this system be trusted, and can management credibly tell us when it is fixed?

Until that question is answered, Alaska Air Group carries a material, unresolved strategic risk embedded in one of its most valuable assets.

What This Report Does Not Claim

This report does not allege fraud or intent.

It does not assign a price target.

It does not speculate on regulatory or litigation outcomes.

It presents evidence that the integrity, auditability, and governability of Alaska’s loyalty programme are legitimately in doubt.

That alone warrants a fundamental reassessment of the business.

SECTION 1: THE 10.40σ ACCOUNTING DISCONTINUITY

Exhibit A: The Statistical Break

In Q2 2025, Alaska Air Group’s loyalty programme issuance-to-revenue ratio deviated 10.40 standard deviations from its historical baseline. This is an extreme statistical outlier with no precedent in Alaska’s history or among peer airlines across 13 quarters of observation.

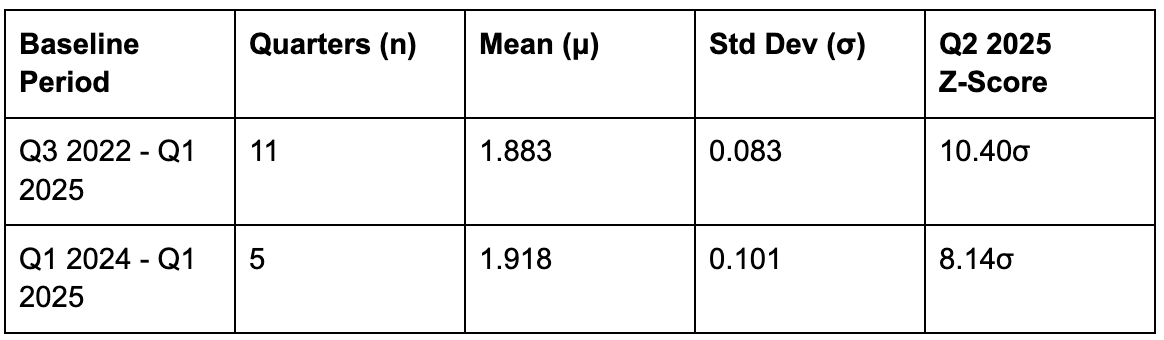

The deviation is unique to Alaska. No peer airline exhibits anything comparable during the same period.

What does this indicate?

When Alaska issues loyalty points, two things normally happen:

A liability is created (the obligation to honour those miles later)

Revenue / profit is recognised (because the partner paying for those miles pays more than they cost to fulfil).

These two figures move in lockstep.

In Q2 2025, they did not. Alaska created $180 million of additional liability with no corresponding profit.

Points were added to the books, but the revenue that should have accompanied them did not appear.

What the Ratio Represents in Dollar Terms

The issuance-to-revenue ratio compares:

“Increase in liability for loyalty points issued” (the dollar value of new loyalty obligations created in the quarter), to

“Loyalty programme other revenue” (the immediate revenue recognised from partner-funded mile issuance).

For the eleven quarters from Q3 2022 through Q1 2025, this ratio was stable with:

Mean: 1.883

Standard deviation: 0.083

In Q2 2025:

Loyalty liabilities increased by $576 million

Loyalty programme other revenue was $210 million

Resulting ratio: 2.743, versus a baseline expectation of approximately 1.88

Had historical economics held, Q2 2025 liability issuance would have been approximately $396 million.

Instead, Alaska created approximately $180 million of additional loyalty contract liability beyond what its own historical relationship to revenue would predict.

This $180 million excess liability creation is the economic substance of the 10.40σ anomaly.

Why This Matters

For eleven consecutive quarters, Alaska’s loyalty programme economics behaved predictably. In Q2 2025, they broke violently and then immediately reverted in Q3 2025.

This pattern is inconsistent with:

gradual economic change

seasonality

merger integration drift

estimation noise

It is consistent only with a discrete, material event concentrated within a single quarter.

The immediate reversion is critical. It rules out structural regime change and indicates that whatever drove the $180 million excess liability creation was either resolved, reversed, deferred, or reclassified.

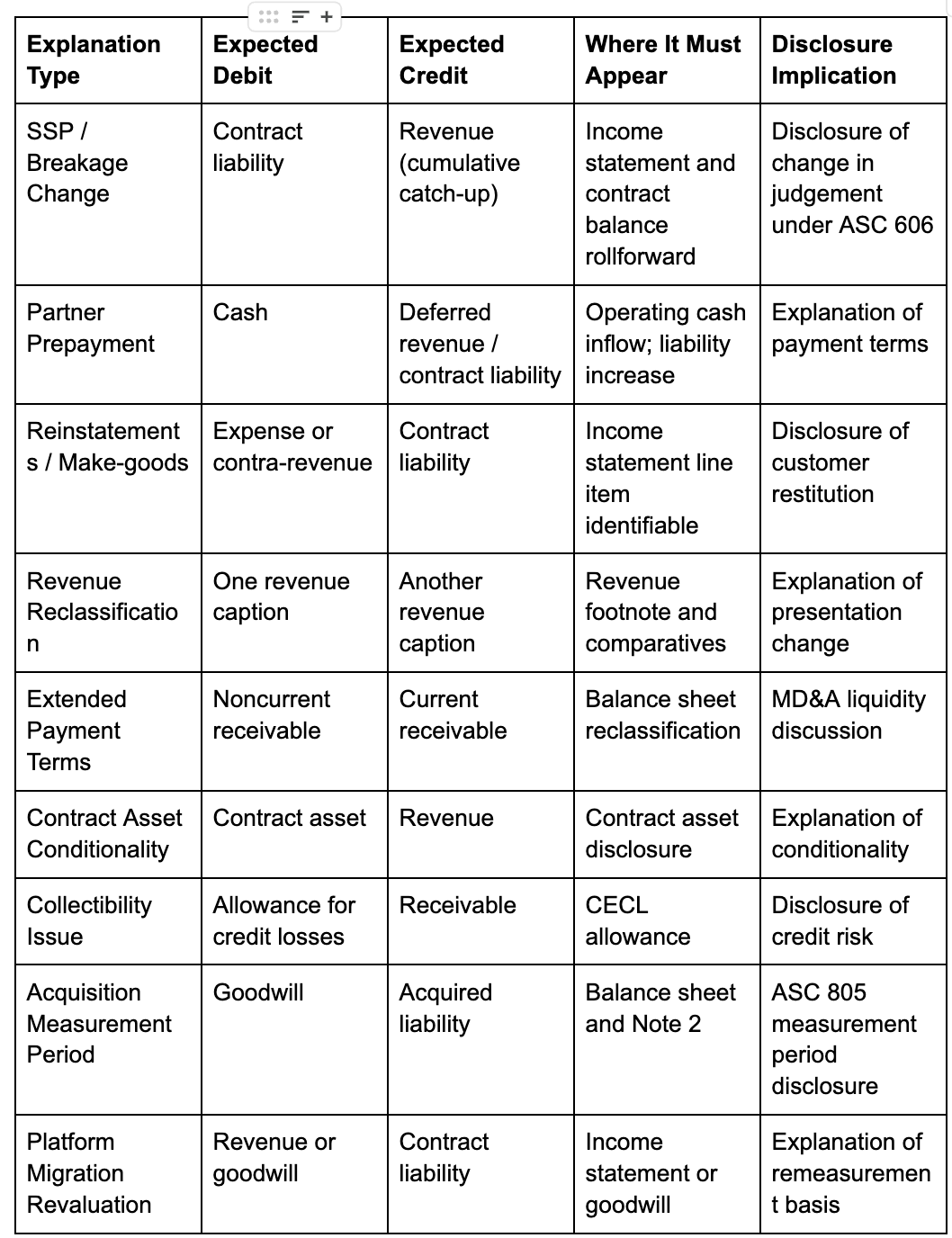

What Could Produce a $180 Million Excess Liability

One accounting mechanism capable of increasing loyalty contract liabilities without a commensurate increase in loyalty programme revenue is issuance without consideration. Examples include reinstatements, make-good credits, or other adjustments not funded by an affinity partner.

At a magnitude of $180 million in a single quarter, such activity would ordinarily be expected to produce:

a clearly identifiable offset in the income statement (expense or contra-revenue), and

interim-period disclosure explaining the nature and cause of the activity.

No such offset or disclosure appears in the Q2 or Q3 2025 filings.

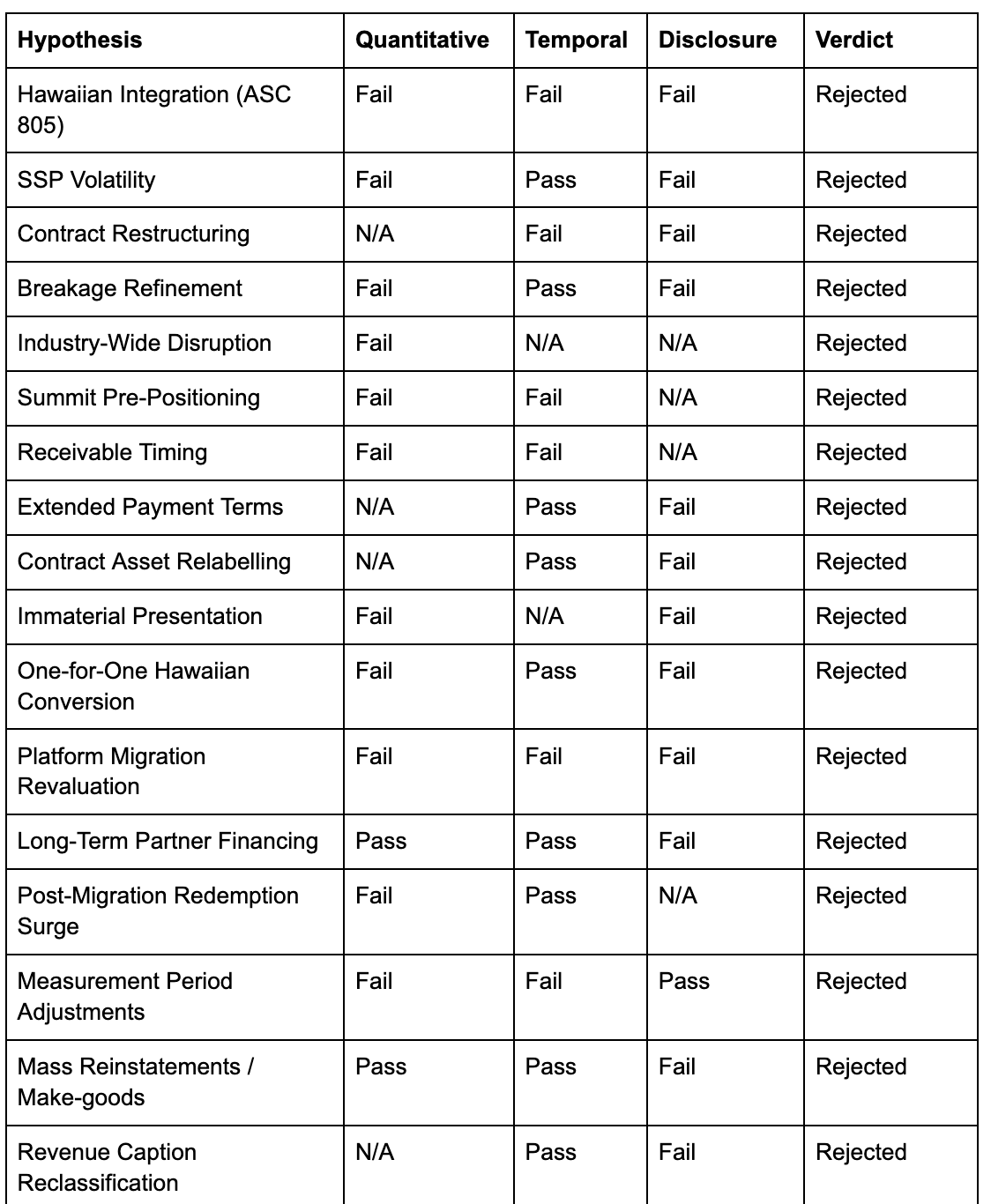

Appendix A.8 evaluates seventeen alternative benign explanations. Each fails on quantitative sufficiency, timing, or disclosure requirements. The $180 million excess liability creation therefore remains unreconciled in the public record.

SECTION 2: THE BALANCE SHEET TRAIL

The Affinity Receivable Spike (Q2 2025)

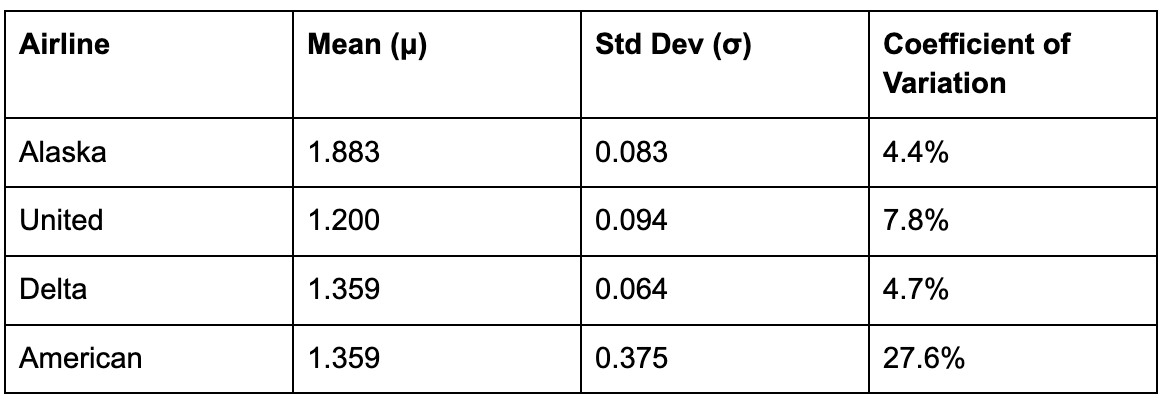

In Q2 2025, amounts due from affinity card partners increased by $195 million in a single quarter.

Bank of America (BofA) is Alaska’s sole credit card partner, and thus make up almost the entirety of affinity card partners. Henceforth, we shall name affinity card partners as BofA for straightforward comprehension.

This $195 million BofA receivable spike is of similar magnitude to the $180 million excess loyalty liability creation identified in Section 1, strongly suggesting interaction between loyalty programme activity and partner settlement flows.

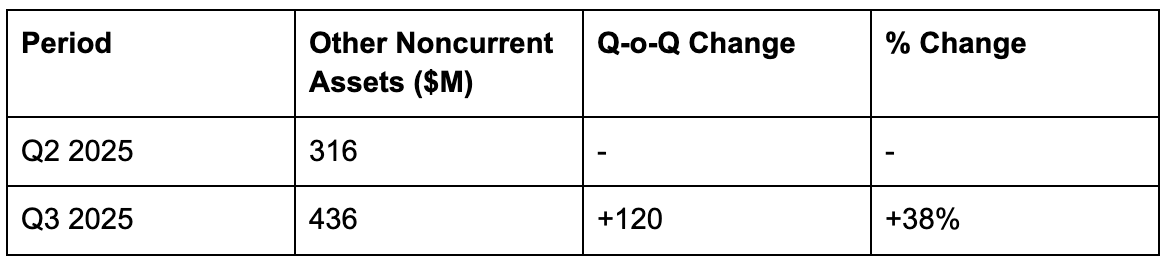

The Non-Current Reclassification (Q3 2025)

Between Q2 and Q3 2025, approximately $120 million migrated into Other Non-Current Assets.

If the Q3 BofA receivable decline reflected ordinary cash collection, a corresponding operating cash inflow would typically be visible as a material operating cash tailwind, absent offsetting working-capital movements of comparable magnitude.

Instead, roughly $120 million of the $195 million BofA receivable spike appears to have been reclassified from current receivables into a non-current balance-sheet category, without explanatory disclosure.

This reflects a change in the nature or expected realisation of the asset, not merely its balance.

The Retroactive Revision

In its Q2 2025 10-Q, Alaska retroactively revised 31 December 2024 BofA receivables from $118 million to $176 million, a $58 million (49%) increase.

The disclosure to this was remarkable. The author could not be less helpful in drawing investor’s attention to the re-stated information that had been made.

“Certain prior period amounts in this note have been revised by an immaterial amount to reflect the appropriate classification of receivables.”

The sophistry extends to even obscuring the number of revisions to look for.

Do not strain your eyes to read the image below, but note the statement’s lack of proximity to the affected number.

Deliberately or by chance, the effect could not obfuscate more.

Critical timing: This revision was disclosed after the Q2 2025 receivable spike, not during the annual audit.

Absent the revision, the Q2 increase would have appeared as a 159% quarter-on-quarter surge. With the revision, it appears as 74%.

The $58 million retroactive adjustment to BofA receivables materially alters trend perception for the same balance-sheet line that spikes in the anomaly quarter. At approximately 15% of Alaska’s 2024 net income, it is qualitatively material under SAB 99 and warrants clear explanation.

The Settlement Constraint

Taken together, the balance-sheet movements imply:

$180 million of excess loyalty liability creation

$195 million of new BofA receivables

$120 million reclassified into non-current assets

$58 million retroactively revised into the prior period

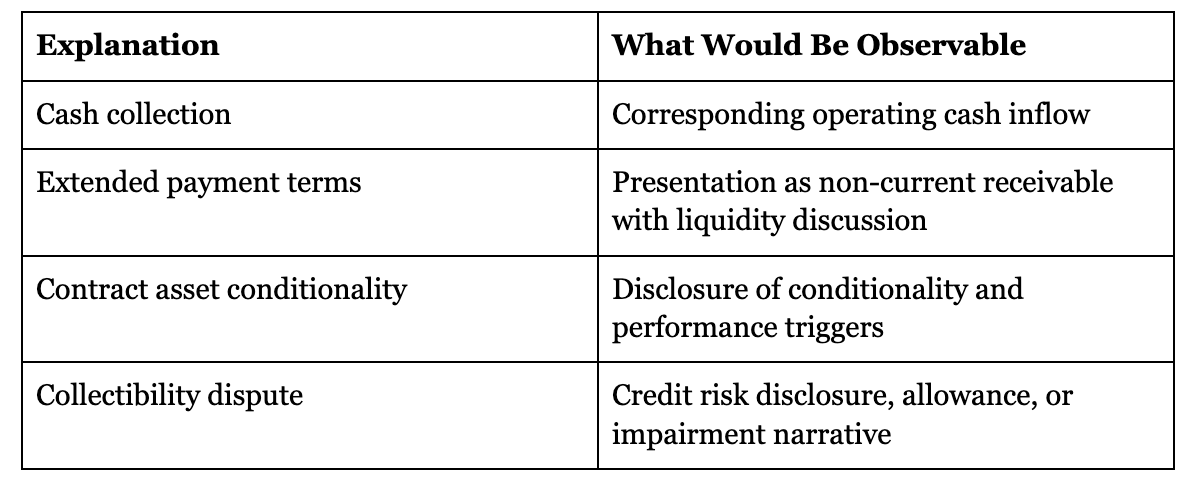

The combined pattern is compatible with only a narrow set of explanations under U.S. GAAP, all of which are observable and falsifiable.

None of these explanations is provided in the filings.

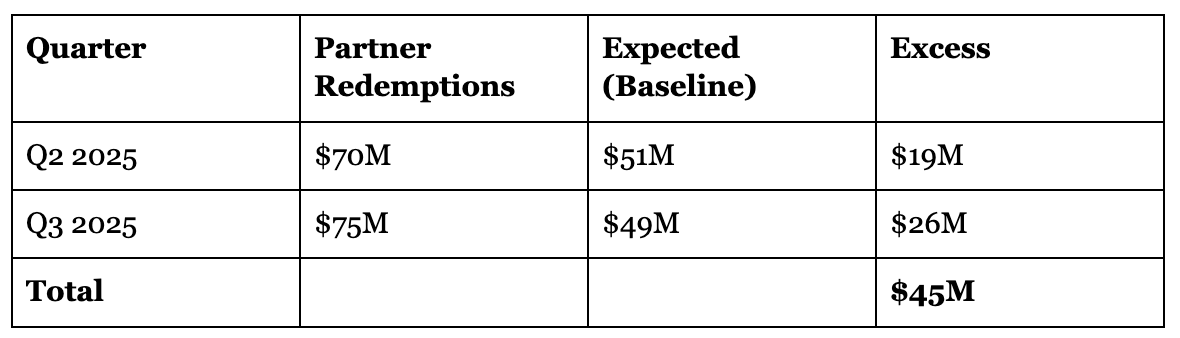

Elevated Partner Redemptions

Across Q2 and Q3 2025, partner airline redemptions exceeded baseline expectations by approximately $45 million.

This excess persists beyond the anomaly quarter itself and overlaps temporally with the balance-sheet reclassification described above.

Commercial explanations remain possible. None are disclosed. Without disaggregation by carrier or redemption type, investors cannot determine whether the $45 million excess reflects benign mix shifts or non-recurring stress within the loyalty programme.

Section 2 Conclusion

Sections 1 and 2 together document a coherent numerical sequence:

$180M of excess loyalty liability created in Q2 2025

$195M surge in BofA receivables in the same quarter

$120M reclassified to non-current assets in Q3

$58M BofA receivables retroactively revised into the prior period

$45M of excess partner redemptions across Q2-Q3

These figures are not estimates. They are arithmetic consequences of Alaska’s published financial statements.

The sequence describes a loyalty programme under acute strain that has not been adequately explained through public disclosures.

SECTION 3: LOYALTY POINTS THEFTS AND PLATFORM FAILURE

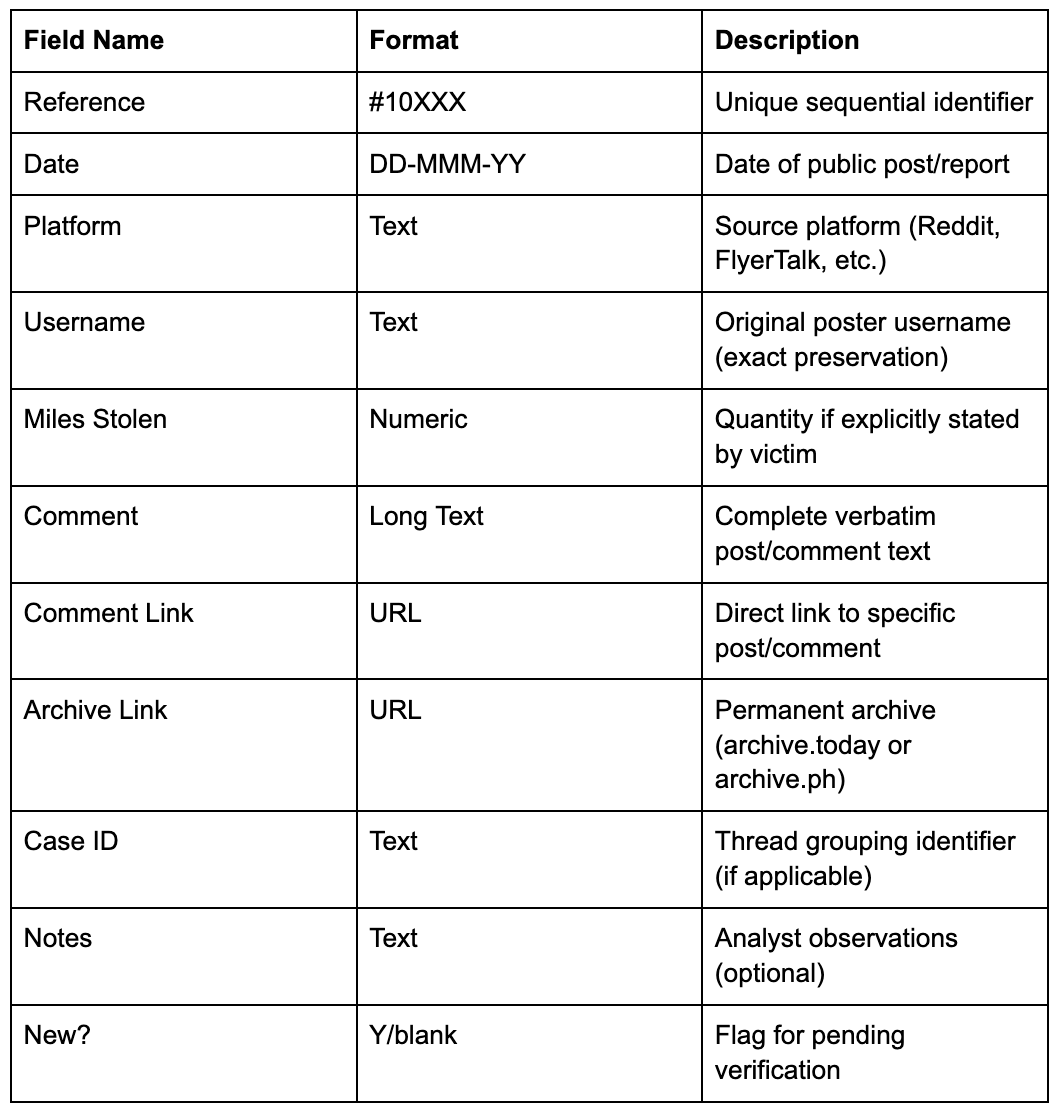

This section analyses publicly reported thefts of loyalty points from Alaska Air Group loyalty accounts during 2025, based on disclosures by affected members across public forums, social platforms, and media coverage. The dataset captures cases where points were actually stolen and redeployed, not attempted or blocked intrusions. Dates reflect when thefts were publicly reported, not necessarily when they occurred.

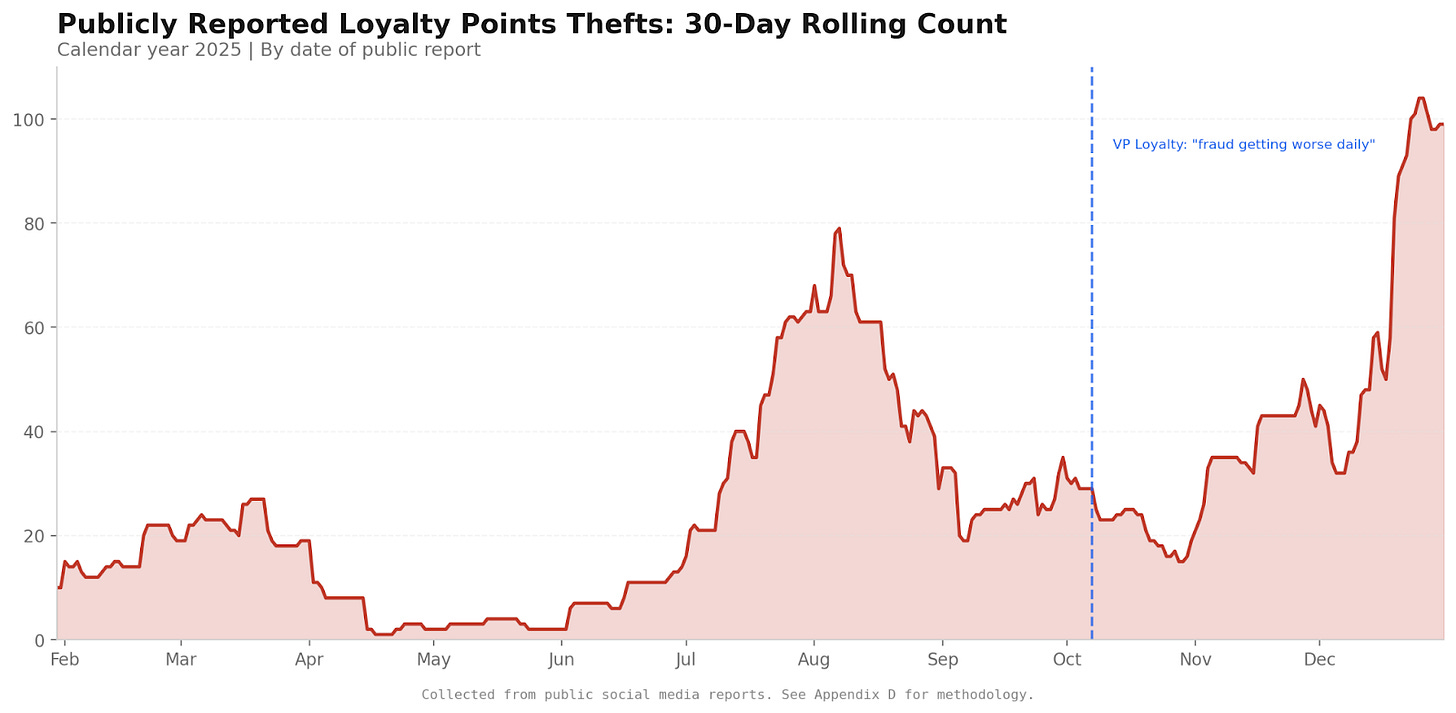

Scale and Acceleration of Loyalty Points Theft Reports

Systematic review of public forums identified approximately 370 loyalty points theft reports during calendar year 2025.

The volume of theft reports increased materially through the second half of the year, with 105 new theft reports in December alone, the highest monthly total observed.

The rolling average exhibits clear step-changes and prolonged plateaus at elevated levels rather than random fluctuation, indicating a sustained increase in the visibility and discovery of loyalty points thefts over time.

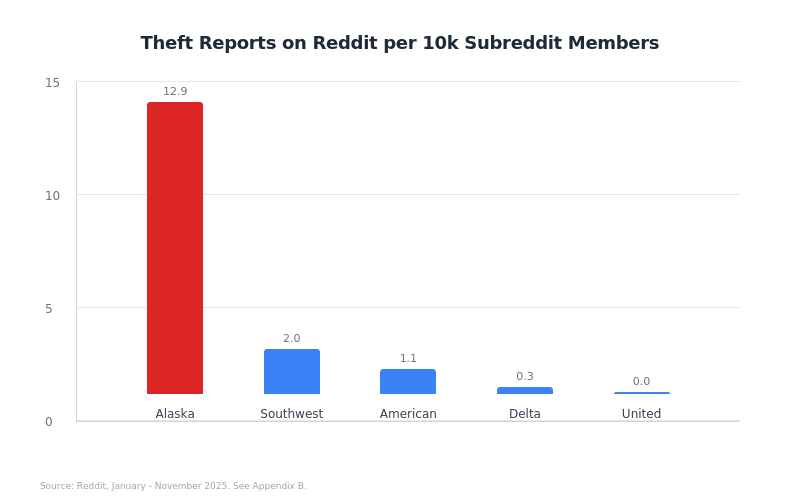

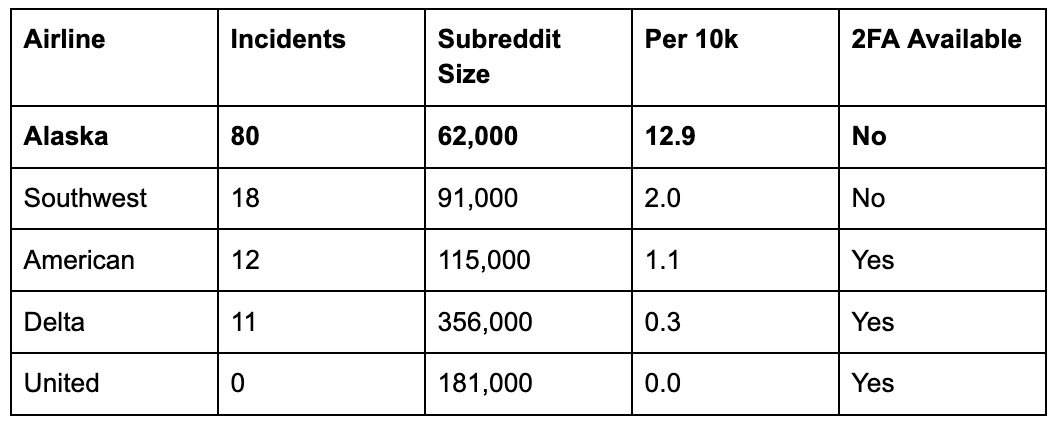

Peer Comparison

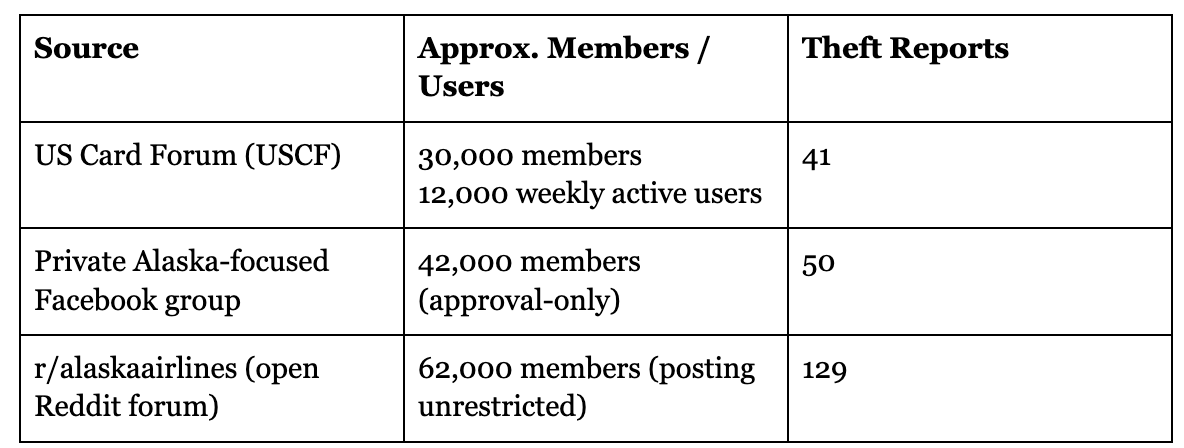

The below table was compiled using a controlled independent methodology principally on Reddit to scholastically compare the frequency of mileage thefts.

Alaska is suffering uniquely from account thefts in 2025.

Alaska, Southwest, American, Delta and United had 80, 18, 12, 11 and zero theft reports respectively over the examined period.

On a normalised basis, Alaska’s loyalty points theft report rate is approximately 23.4× higher than peer airlines using the same source and methodology.

Where the Theft Reports Came From

The 370 publicly reported loyalty points thefts did not surface evenly across open, high-traffic platforms. A material share emerged from small, gated, or linguistically isolated communities relative to Alaska’s disclosed ~12 million (based on 11 million disclosed in Dec 2024 by management and heady reviews of growth since) active loyalty members.

The remaining reports were scattered across FlyerTalk threads, Facebook comments, and isolated forum posts.

220 of the 370 reported thefts, 60%, came from relatively obscure corners of the internet, with a combined user base of 134,000 users.

The most probative signal comes from US Card Forum (USCF). USCF is a niche, Chinese-language credit-card optimisation forum where Alaska is not a focal topic and airline loyalty is incidental. 41 loyalty points theft reports originated from here alone.

Against that backdrop, the absence of theft reports from the overwhelming majority of Alaska’s ~12 million active members cannot reasonably be interpreted as absence of theft.

The observed 370 theft reports are therefore best understood as a visibility sample, not a census. Interpreted in context, they are far more consistent with the tip of an iceberg than with a small or isolated issue.

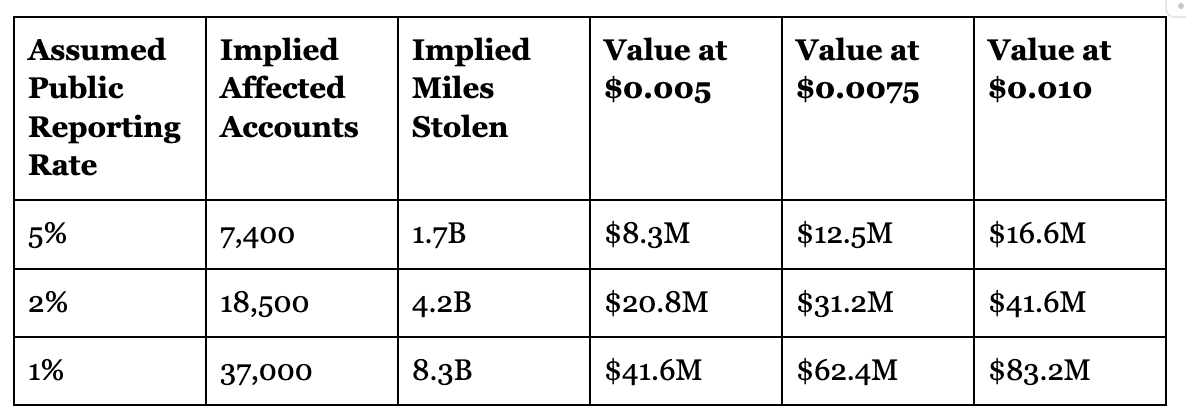

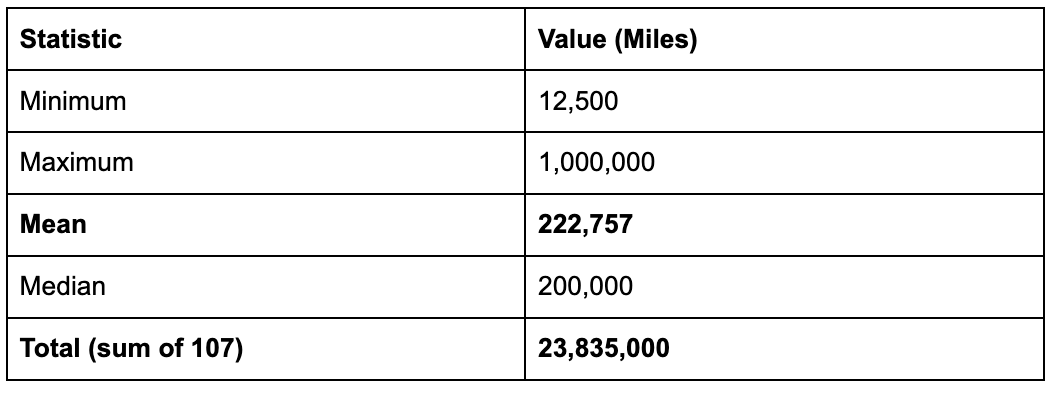

Illustrative Scale and Loyalty Value at Risk

The table below illustrates the implications of the observed theft reports under conservative assumptions about public reporting behaviour. These figures do not represent realised losses. Fraudulent award bookings may be cancelled if detected prior to travel. The table is intended to show the order of magnitude of loyalty value placed at risk, not ultimate expense.

However if not detected prior to travel, Alaska must reimburse the partner airline. When the member is reimbursed, the fraud expense must be borne by Alaska, as the loyalty points will be spent again in the future by the member.

Assumptions:

Observed theft reports: 370

Average miles reported stolen per account: 224,861

Illustrative SSP range: $0.005 to $0.010 per mile

Implied miles = affected accounts × 224,861 average miles per reported case.

Even under conservative assumptions, the implied scale is inconsistent with a trivial or isolated issue relative to a loyalty programme with ~12 million active members.

Mode of Loyalty Points Theft

Attack Characteristics

Target: Partner airlines

Cabin: Premium

Timing: <48 hours before departure

Average theft: 224,861 miles

Notification muzzling: Notification email switched so member unaware of booking

Thefts involve cash expenses for Alaska for the reimbursement they must provide partner airlines.

Repeated Evidence Refuting User Negligence or Credential Stuffing

PIN Bypass: Accounts compromised despite Alaska’s mandatory PIN lock already in place.

Same-Day Repeat Compromise: One account hacked twice in one day, with password change between incidents.

Session Hijacking: HackerNews user reported logging in and was randomly granted access to other customers’ accounts. Four months later, the vulnerability persisted.

Implied PII Data Breach

If thousands of high balance accounts have been breached, this implies that a multiple of the accounts that have been drained must have been accessed to ascertain the points balance within.

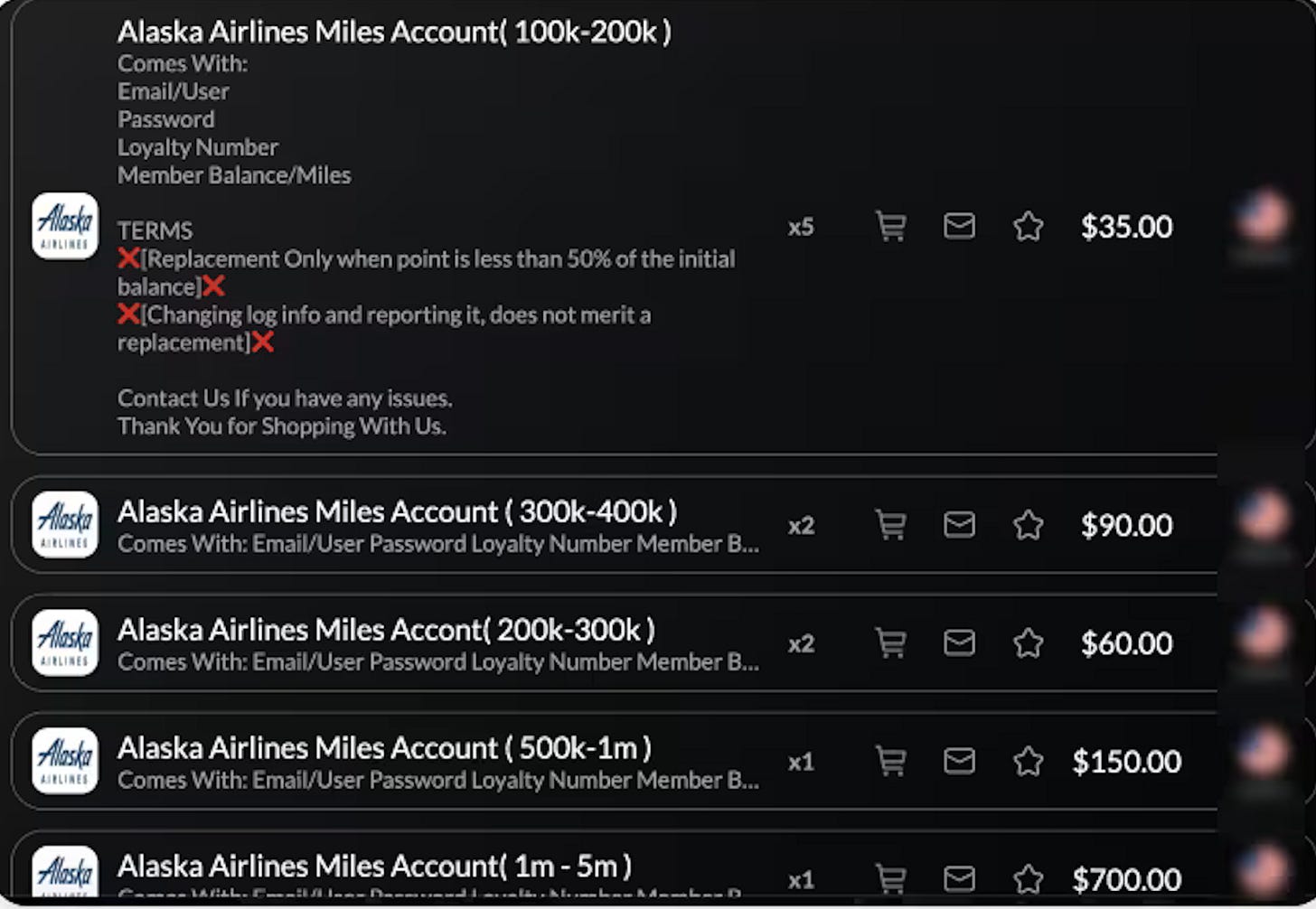

Hacked Accounts for Sale

The compromised accounts for sale were seen by NordVPN for sale on the dark web.

Note 100k to 200k loyalty points is sufficient for a long-haul business class flight. Available for just $35.

Alaska’s Response

The documented incidents have generated observable corporate responses. The nature and timing of these responses raise questions.

Victim documentation reveals standardised response:

Miles restored upon identity verification

Characterised as “one-time courtesy”

Warning: “We will not help you again”

Victim’s accounts are sanctioned with telephone-only access to book award miles.

The consistency suggests formal policy designed to meet frequent incidents. One CSR is quoted saying on hacked account victims “she has to do this 3-5 times per day“.

The policy to restrict victim’s accounts can be found back in April 2022 and has been a consistent response since.

Management Commentary

Press coverage of the phenomenon by Fox13 Seattle and KIRO 7 in July and the Seattle Times in November yielded only generic replies from Alaska and no meaningful engagement.

However Alaska VP of Loyalty announced on 7th October 2025 on Reddit that:

“fraud attempts are getting worse almost daily. It’s something we take very seriously, and it has visibility all the way up to our CEO.”

The 23rd June 2025 Hawaiian Airlines cyberattack’s latest reference in Q3 2025’s 10Q was:

“we do not believe the incident had ... a material impact ... The investigation remains active ... unable to determine the full impact [yet]”

After multiple IT outages that grounded flights, Alaska engaged Accenture on 31st October for a “comprehensive audit of its technology systems”. Remarkably the incident was used as rationale to cancel, not postpone, the earnings call.

However the CFO provided the first commentary on the Accenture engagement on 4th December 2025

“we don’t have a systemic architecture failure... Have we just under-resourced ourselves? That’s not what they [Accenture] found.”

“Hygiene” and “[an excess] of innovation” were cited as contributory factors to the outages:

“...launched a brand new loyalty platform... and needed to make a lot of updates to our technology, our apps, our website”

Notably the new platform’s 20th August launch did nothing to inhibit the volume of loyalty points thefts in our collection of hacked accounts.

The direct response on IT infrastructure represents a de facto statement that compromised accounts are not a critical identified issue in the current audit.

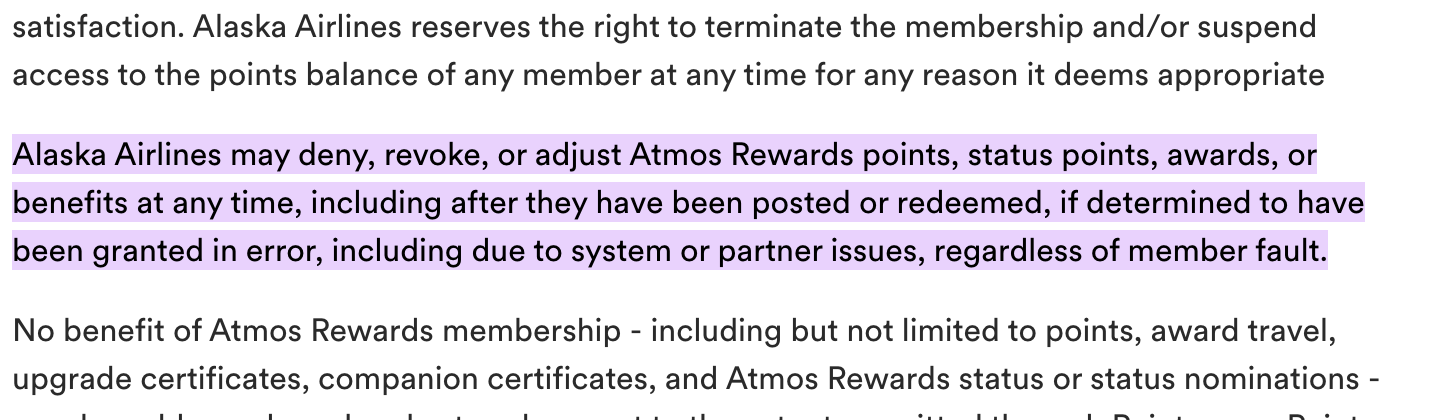

The Signalling in a Terms Change

Alaska recently made an alteration to the terms to their loyalty programme, adding a standalone paragraph (archive).

On 11th September 2025, and before, this term was notably absent:

The additional paragraph, the sole non-cosmetic update to the terms, has a clear meaning.

“Due to system or partner issues” - Alaska’s own system flaws are no longer to be blamed.

“Including after posted or redeemed” - refunded miles can now be un-refunded.

“Regardless of member fault” - victims being blameless for account thefts is no longer a reason for reimbursement.

This defensive legal firewall specifically relates to the ability to remove, or not replenish, loyalty points lost by a blameless member through system issues.

SECTION 4: THE PATTERN OF SYSTEMIC FAILURE

Sections 1 through 3 documented three independent classes of evidence:

An extreme, one-quarter accounting discontinuity in loyalty liabilities and partner balances.

A sustained pattern of loyalty points theft, materially visible across narrow and unrepresentative public channels.

Management acknowledgement of worsening theft activity alongside disclosures and commentary that frame technology issues as isolated, non-systemic, or infrastructure-bound.

Each of these categories could, in isolation, be dismissed as idiosyncratic.

Taken together, they cannot.

A Single System Under Strain

The accounting anomaly, the balance-sheet movements, and the loyalty points thefts all concentrate in the same economic system: Alaska Air Group’s loyalty programme and the technology that governs it.

Loyalty liabilities increased by approximately $180M beyond historical expectations in a single quarter.

BofA receivables increased by $195M in the same period, followed by a $120M migration into non-current assets without explanatory disclosure.

Loyalty points theft reports surfaced repeatedly across small, gated, and low-visibility communities, inconsistent with a trivial or isolated issue given the scale of the loyalty membership.

Management publicly acknowledged that theft attempts were worsening “almost daily,” while formal disclosures and third-party reviews focused on infrastructure resilience rather than account-level integrity.

These observations are not independent. They are linked by the common requirement that the loyalty programme operate as a closed, controlled, and auditable system.

The Control Question

A loyalty programme functions as a private currency. Its value depends not only on marketing appeal or partner breadth, but on control:

Control over issuance

Control over redemption

Control over adjustment and remediation

Control over account access

The evidence presented in this report shows stress across all four dimensions, within a narrow timeframe, without sufficient disclosure to enable investors to reconcile cause, scope, or resolution.

This is not a question of intent. It is a question of whether the system is operating within controlled bounds.

What This Section Establishes

This section does not allege fraud.

It does not assert causation.

It does not speculate on motive.

It establishes that the accounting anomaly, the balance-sheet movements, and the loyalty points thefts form a coherent pattern of system-level failure that cannot be dismissed as noise or coincidence.

SECTION 5: WHAT MUST BE TRUE

Sections 1 through 4 establish a tight numerical and operational pattern. The purpose of this section is to state, as directly as possible, what the published financial statements imply.

The reconciliation gap

In Q2 2025, Alaska created approximately $180M of loyalty contract liability beyond what its historical relationship to loyalty revenue would predict. In the same quarter, BofA receivables increased by $195M. In Q3, approximately $120M migrated into Other Non-Current Assets without disaggregation, while partner redemptions remained elevated.

These are not isolated curiosities. Together they form a reconciliation gap: a material set of loyalty and partner balance movements that cannot be explained from public disclosures.

The limited set of permissible explanations

Based on U.S. GAAP mechanics and standard disclosure practice, only four explanation classes exist:

A material change in loyalty accounting judgements (allocation, estimates, or classification), which would ordinarily be explained as it affects revenue timing and contract balances; or

A material change in BofA settlement or collectibility, which would ordinarily be explained through classification, ageing, and liquidity discussion; or

A material issuance of loyalty obligations without corresponding consideration, which would ordinarily have an identifiable income statement offset; or

A presentation failure, where the financial statements do not faithfully depict the underlying transaction flows and therefore require correction or reclassification.

No other explanation class can mechanically produce the observed combination of: (i) a one-quarter 10.40σ break, (ii) a $195M receivable surge, (iii) a $120M non-current migration, and (iv) elevated partner redemptions.

Why this matters to investors

The investment issue is not which of the four categories proves correct. It is that investors cannot determine which category is operating, because the disclosures provided are insufficient to reconcile the movements.

That uncertainty sits inside the company’s most strategically important asset: the loyalty programme and its partner funding mechanics.

Until Alaska provides a disaggregated rollforward of loyalty contract liabilities, a counterparty-level explanation of BofA receivable movements, and a composition bridge for the $120M increase in non-current assets, the reconciliation gap remains unresolved.

SECTION 6: STRATEGIC RISK IMPLICATIONS

The anomalies described in this report do not exist at the periphery of Alaska Air Group’s business. They concentrate on the company’s most strategically important asset: its loyalty programme.

This section examines the risks that arise not from any single accounting outcome, but from the interaction between platform fragility, partner economics, and customer trust.

The Centrality of the Loyalty Programme

Alaska’s loyalty programme is not a marketing accessory. It is a core economic engine.

The programme:

Generates material cash inflows independent of passenger traffic

Anchors the company’s most profitable customer cohort

Underpins strategic partnerships with financial institutions and airline partners

Functions as a private currency with implicit guarantees of usability, security, and fairness

A programme with these characteristics is only as strong as its credibility. Confidence in the integrity of balances, the reliability of access, and the fairness of remediation is not optional. It is foundational.

The anomalies identified in Sections 1-5 directly affect this foundation.

Credit and Counterparty Sensitivity

The loyalty programme’s economics rely on counterparties behaving predictably.

BofA partners must be willing to fund issuance. Airline partners must be willing to honour redemptions. Settlement flows must be trusted to clear without dispute.

When loyalty liabilities rise sharply without corresponding clarity on funding or settlement mechanics, questions naturally arise about:

Timing and collectibility of partner balances

Allocation of losses arising from extraordinary events

Whether certain costs are being absorbed internally rather than transparently recognised

These questions are not hypothetical. They are implicit in already observed balance sheet movements.

A loyalty programme that begins to accumulate unresolved partner balances or deferred classifications introduces latent credit risk into what is otherwise perceived as a clean, cash-generative model.

The Perverse Economics of Remediation

Alaska’s response to platform failure systematically penalises its most valuable customers.

High-balance members are disproportionately targeted because they hold the currency worth stealing. After restoration, they face permanent telephone-only booking restrictions, hold times averaging over 90 minutes, and one-hour access windows during business hours. They bear these restrictions indefinitely, regardless of subsequent password changes or PIN protections. And they are warned that restoration was a “one-time courtesy” unlikely to be repeated.

The commercial effect is to convert a platform failure into a customer penalty. The miles remain on the books, but their utility has been materially impaired for precisely those members whose lifetime value justifies the co-brand economics.

No competitor has imposed comparable restrictions. No peer airline operates without two-factor authentication. The contrast is visible to every affected customer and increasingly visible to the communities where they share their experiences.

Loyalty programmes do not fail suddenly. They fail gradually, as the customers who matter most quietly migrate to alternatives that treat their balances as assets worth protecting.

The Compounding Nature of Platform Risk

The risks described in this section do not operate independently. A platform that cannot reliably secure accounts creates remediation costs that stress partner settlements. Partner settlement anomalies raise questions that affect counterparty confidence. Counterparty uncertainty accelerates customer migration. And customer migration undermines the membership base that justifies the co-brand relationship.

This is the nature of platform risk: it compounds. The question is not whether Alaska will face a reckoning. The question is whether the reckoning has already begun, and whether the disclosures provided allow investors to assess its scope.

SECTION 7: FINAL CONCLUSION

This report does not allege fraud.

It does not speculate about intent.

It does not rely on extrapolated penalty arithmetic, litigation modelling, or regulatory outcomes.

It does something simpler and more consequential.

It identifies a set of material facts that must be reconciled if confidence in Alaska Air Group’s loyalty programme is to be restored.

The Same Facts, Seen in Full

As set out in the Executive Summary and examined in detail in Sections 1 through 7, two independent phenomena stand out:

A 10.40 standard deviation break in loyalty accounting behaviour in Q2 2025, unprecedented in Alaska’s history and among peer airlines, appearing for a single quarter and immediately reverting.

A persistent, accelerating pattern of publicly reported loyalty point thefts, acknowledged by management as “getting worse almost daily”, accompanied by repeated indicators of system-level access failure and compensatory customer restrictions.

Either of these facts, in isolation, would warrant explanation.

Taken together, they cannot be dismissed as coincidence.

The Accounting Constraint Revisited

A 10.40σ deviation is not noise. It is not seasonality. It is not integration drift. It is not estimation volatility.

It is a statistical impossibility under normal operating conditions.

Under U.S. GAAP, a deviation of this magnitude can arise only from a discrete, material event affecting loyalty liabilities, partner settlements, or both. Yet Alaska’s public disclosures do not allow investors to reconcile:

Why loyalty liabilities increased by approximately $180M beyond historical expectations

Why BofA receivables increased by $195M in the same quarter

Why $120M subsequently migrated into non-current assets

Why a $58M prior-period BofA receivable revision was disclosed only after the anomaly quarter and characterised as immaterial

As stated in the Executive Summary, one of four explanations must be true. There is no fifth option. None is explained with sufficient specificity to permit reconciliation.

Platform Integrity Is Now Central, Not Peripheral

The publicly reported loyalty account thefts documented in 2025 are not sporadic complaints. They are sustained, accelerating, and explicitly acknowledged by senior management.

They exhibit features inconsistent with isolated user error:

Repeated unauthorised access despite credential changes

Session-level anomalies and cross-account visibility

Thefts have been reported despite PIN-based account locks.

Customer remediation practices that restrict access rather than resolve

These are hallmarks of architectural fragility, not behavioural misuse.

At this point, the relevant question is no longer whether Alaska has experienced a cybersecurity issue. It is whether the loyalty platform can reliably enforce account boundaries at all.

A Single System, Multiple Failures

This report deliberately refrains from asserting causation. However, it is not neutral on coherence.

The accounting discontinuity, the balance-sheet movements, the customer remediation practices, the targeted amendment to programme terms, and the platform-level failures all concentrate in the same system: the loyalty programme and its underlying technology.

To treat these as unrelated requires accepting a series of implausible coincidences:

An extreme accounting break unrelated to operational disruption

Settlement anomalies unrelated to loyalty activity

Platform access failures unrelated to customer remediation

Legal term changes unrelated to system shortcomings

That interpretation strains credibility.

The simpler and more coherent explanation is that Alaska’s loyalty platform is not operating as a closed, fully controlled, auditable system, and that its weaknesses are cascading across accounting, customer experience, and partner economics.

This does not require malice. It requires only an IT system that cannot see, cannot segment, and cannot reliably control access in real time.

The Strategic Consequence Reaffirmed

A loyalty programme functions as a private currency. Its value rests on trust:

Trust that balances are secure

Trust that access is reliable

Trust that failures will be corrected fairly

The evidence in this report shows that all three pillars are under strain.

High-value customers bear the cost of failures they did not cause. Partner economics show signs of stress. And the disclosures provided do not allow investors to understand how, or whether, these issues have been resolved.

The Question That Must Be Answered

The central question for investors, stated at the outset of this report, remains unchanged:

Can this system be trusted, and can management credibly tell us when it is fixed?

Until Alaska explains:

what caused the Q2 2025 accounting discontinuity

how loyalty liabilities were created and funded in that quarter

why partner balances behaved as they did

how many accounts have been stolen from

and whether the loyalty platform can reliably enforce account integrity

The market is being asked to accept on faith what the numbers, the loyalty point thefts, and the customer experience all contradict.

That is not a sustainable position.

The 10.40σ accounting anomaly must be answered for.

The platform integrity failure must be answered for.

Until they are, Alaska Air Group carries a material, unresolved strategic risk embedded in one of its most valuable assets.

A Direct Final Note From the Author

I first read of an Alaska victim’s experience of being hacked, and Alaska’s remediation process 4 months ago. Many others emerged to console that they had an almost identical experience.

What bothered me enough then was what started me pulling on all the threads that led to today:”Why can’t Alaska stop the thefts?

In April 2022, we can read a story of theft and Alaska policy response that is identical to today. Even down to the permanent PIN lock and one-time courtesy refund.

Nearly four years later,, the rate of thefts appears to be accelerating faster than ever, and Alaska has been unable to do anything about it, so just continues to penalise the victims like they have always done.

The hypothesis I formed then has hardened now into a firm deduction. I have uncovered no evidence to support it, but I can see no other explanation:

Alaska Airlines IT systems are so palsied that they are unable to stop the thefts.

For any company, this would be a crisis.For an airline, in my view, this makes Alaska uninvestable.

Note: Consistent with the gravity of these findings, a formal whistleblower complaint has been filed with the SEC on January 4th 2026, detailing the accounting anomalies and disclosure failures documented in this report.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tommy Caton was co-founder, Chief Revenue Officer, and Chief Financial Officer of travel data analytics firm AirDNA from 2015 to 2022. He holds an MBA in finance from the Kellogg School of Management (Northwestern University) and worked for four years in KPMG’s Corporate Finance division.

The author is not a professional short seller. This analysis originated from noticing irregularities in publicly available information, which led to taking a short position in Alaska Air Group. Aside from this stock, 100% of investable assets are in diversified funds. However, that does make me a short-seller. Weigh that up, as you weigh up my words.

Download the Full Report.

APPENDICES

Appendix A: Detailed Accounting Methodology and Null Hypothesis Testing

Appendix B: Theft Databook Compilation Methodology

Workbook A: Calculations Spreadsheet

Workbook B: All 370 documented thefts with archive links to their source.

APPENDIX A: Statistical Methodology and Peer Comparison Data

A.1 Issuance-to-Revenue Ratio Calculation

This ratio is a useful analytical proxy for the underlying economics of the loyalty programme under ASC 606. It is not a metric defined or required by the standard itself.

The ratio is calculated as:

Ratio = Increase in liability for loyalty points issued (quarterly) / Loyalty programmeOther Revenue (quarterly)

Data is extracted from Alaska Air Group 10-Q and 10-K filings, specifically:

“Increase in liability for loyalty points issued” from Note 3: Revenue

“Loyalty programme other revenue” from segment revenue disclosures

Quarterly figures for cumulative YTD disclosures are derived by subtracting prior quarter YTD figures.

A.2 Baseline Period Selection

The baseline period (Q3 2022 through Q1 2025) was selected based on: availability of consistent disclosure format post-ASC 606 implementation; exclusion of pandemic-affected periods; inclusion of sufficient observations for statistical validity (n=11); and termination before the anomaly quarter.

A.3 Statistical Analysis

Z-Score Calculation:

Z = (X - μ) / σ

Where:

X = Observed Q2 2025 ratio (2.743)

μ = Baseline mean (1.883)

σ = Baseline standard deviation (0.083)

Z = (2.743 - 1.883) / 0.083 = 10.40

Sensitivity Analysis:

All specifications yield Z-scores exceeding 8σ. The finding is robust to baseline selection.

A.4 Peer Comparison Methodology

Quarterly issuance-to-revenue ratios were calculated for United Airlines (UAL), Delta Air Lines (DAL), and American Airlines (AAL) using identical methodology applied to their respective SEC filings.

Baseline Statistics (Q3 2022 - Q1 2025):

A.5 Balance Sheet Movements

Affinity Card Receivables:

Other Noncurrent Assets:

Cash Flow Corroboration:

The Q2 2025 cash flow statement shows a use of operating cash of approximately $171M for accounts receivable movements, confirming the receivables spike was non-cash in nature. The subsequent Q3 2025 receivables decline did not generate corresponding operating cash inflow, supporting the inference that the asset was reclassified rather than collected.

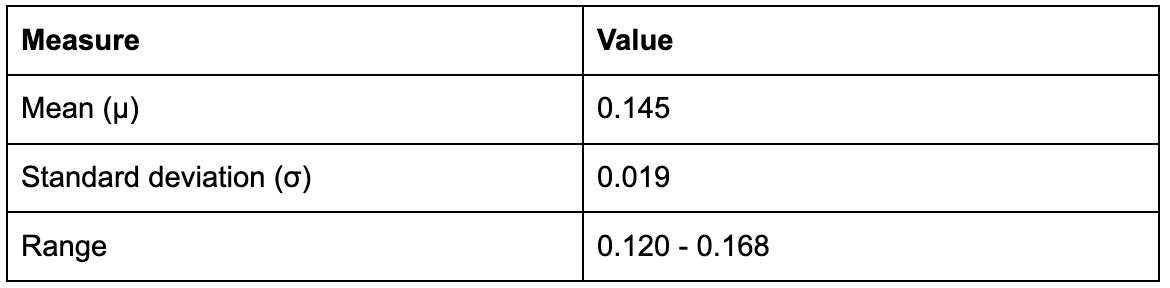

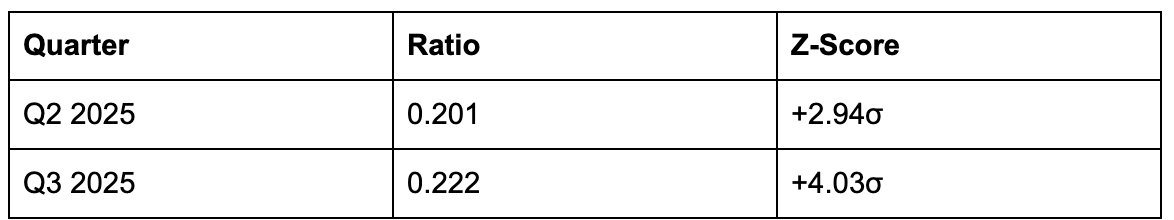

A.6 Partner-to-Passenger Redemption Ratio Methodology

The partner-to-passenger redemption ratio provides a merger-normalised metric for assessing whether partner redemptions are elevated relative to overall redemption activity.

Ratio Calculation:

Ratio = Loyalty redemptions - Partner Airlines (quarterly) / Loyalty redemptions - Passenger Revenue (quarterly)

Rationale:

Both partner and passenger redemptions should scale proportionally with the merged entity’s larger membership base. If the Hawaiian merger simply added Hawaiian’s loyalty economics to Alaska’s, the ratio should remain stable. Deviations from the historical ratio therefore indicate changes in the composition of redemptions rather than mere scale effects from the merger.

Baseline Statistics (Q1 2024 - Q1 2025):

The Q3 2025 deviation of 4.03 standard deviations has a probability of less than 0.005% under normal distributional assumptions.

A.7 Limitations

This analysis was conducted using publicly available SEC filings. The following information was not available and would be required for definitive conclusions: internal accounting memoranda and judgement documentation; Bank of America contract terms and amendments; detailed composition of Other Noncurrent Assets; partner compensation expense detail by carrier; and management explanations for observed patterns.

A comprehensive forensic audit with management access would be required to definitively determine the cause and precise magnitude of the patterns identified. Management may have information and rationales not apparent from public disclosures that differ from the interpretations presented here.

A.8 Null Hypothesis Exploration

Before concluding that the Q2-Q3 2025 accounting patterns warrant concern, a responsible analysis must consider whether benign explanations could account for the observations. This section examines 17 alternative hypotheses that might be offered to explain the 10.40σ statistical anomaly, the $195M receivables spike, and the subsequent $120M reclassification to noncurrent assets. Each hypothesis is assessed against what the numbers would need to show if true, and what GAAP would require to be disclosed.

The framework applied to each hypothesis is straightforward. If a benign explanation is correct, it must be consistent with the quantitative data, temporally plausible, and accompanied by the disclosures that GAAP requires for material transactions of that nature. Failure on any criterion suggests the explanation is inadequate.

Hypothesis 1: Hawaiian Airlines Integration Accounting

The Benign Explanation

The Hawaiian Airlines acquisition closed on 18 September 2024. Complex acquisitions involve purchase price allocations, fair value adjustments, and measurement period refinements under ASC 805. An observer might reasonably assume that the Q2 2025 loyalty programme anomalies reflect integration accounting noise from absorbing Hawaiian’s HawaiianMiles program.

What Would Need to Be True

If integration accounting caused the Q2 2025 anomaly, the following signatures would be expected. The loyalty programme ratio deviations would have appeared immediately after the September 2024 acquisition close, or at least shown a gradual trend through Q4 2024 and Q1 2025 as integration progressed. Any measurement period adjustments affecting loyalty accounting would be disclosed in Note 2 (Business Combinations), as required by ASC 805-10-50-2(h). The MD&A would explain integration impacts on loyalty programmes other revenue and related balance sheet items.

Why It Fails

The timing is inconsistent with an integration explanation. Q4 2024 and Q1 2025 ratios were 2.02 and 2.00 respectively, both within normal ranges and showing no anomaly. The 10.40σ deviation appeared only in Q2 2025, eight months after the acquisition closed, then immediately reverted to 1.87 in Q3 2025. This single-quarter spike followed by complete normalisation is inconsistent with gradual integration effects.

The filing states that no material ASC 805 measurement period adjustments were recorded during the quarter. This limits the plausibility of a late purchase accounting true up as the driver of the observed anomaly. It does not, however, preclude post close operational integration effects, such as programme harmonisation, award chart changes, partner settlement mechanics, IT migrations, or customer conversion incentives. If Hawaiian integration is the explanation, it would therefore need to operate through such operational mechanisms rather than through purchase accounting adjustments, and would still be expected to support a coherent commercial and accounting narrative if material.

GAAP Reference: ASC 805-10-50-2(h) requires disclosure of material effects of acquisitions on reported results. No such disclosure links the Q2 2025 anomaly to Hawaiian integration.

Verdict: ASC 805 measurement period accounting does not explain a one quarter, isolated 10.40σ event appearing eight months after acquisition close; any integration based explanation would need to be operational in nature and should still support a coherent disclosed narrative if material.

Hypothesis 2: Standalone Selling Price Volatility

The Benign Explanation

Under ASC 606, Alaska must allocate the cash received from Bank of America between a marketing component (recognised immediately as revenue) and a transportation component (deferred until miles are redeemed). This allocation depends on the estimated standalone selling price (SSP) of the transportation element. An observer might suggest that Alaska refined its SSP estimate in Q2 2025, causing more of each dollar received to be allocated to deferred revenue rather than immediate recognition.

What Would Need to Be True

The issuance to revenue ratio is an analytical proxy rather than a direct accounting metric. If one assumes, illustratively, that the observed ratio movement were driven primarily by changes in allocation economics such as SSP, the implied change would be very large by industry standards. However, the ratio can also be affected by mix effects, classification timing, and changes in partner economics. Accordingly, the implied percentage should be interpreted as an order of magnitude indicator rather than a precise inferred SSP revision.

Why It Fails

No disclosure of any SSP or breakage assumption change appears in the Q2 2025 10-Q. Alaska’s 2024 10-K provides sensitivity analysis on key loyalty assumptions, but no Q2 2025 update references any change. The implied magnitude of any SSP shift, if one assumes allocation economics are the primary driver of the proxy movement, would be exceptionally large by industry standards. However, because the ratio can be influenced by mix, timing, classification, and partner economics, the proxy cannot be reverse engineered into a single precise SSP percentage change with confidence.

Furthermore, if Alaska genuinely changed its SSP estimate by this magnitude without disclosure, that would itself constitute a GAAP violation under ASC 606-10-50-17. The hypothesis thus fails the “GAAP trap”: either no material change occurred (leaving the anomaly unexplained), or a material change occurred without required disclosure (constituting a compliance failure).

GAAP Reference: ASC 606 10 50 17 through 50 20 require disclosure of the significant judgements, and changes in judgements, that affect the determination of the amount and timing of revenue recognition. While the Codification does not require registrants to restate or highlight every quarterly change in judgement, a material change in SSP, breakage assumptions, or other key loyalty programme judgements that materially affects reported results would ordinarily be explained in the interim period narrative disclosures.

Verdict: SSP volatility fails both quantitative plausibility (35-40% single-quarter shift is economically implausible) and the disclosure test (no change was disclosed).

Hypothesis 3: Bank of America Contract Restructuring

The Benign Explanation

Alaska’s Mileage Plan generates most of its loyalty revenue through its co-branded credit card partnership with Bank of America. An observer might suggest that Q2 2025 reflected a contract restructuring with Bank of America, perhaps a pre-payment arrangement, modified pricing structure, or advance purchase of miles ahead of a new card product launch.

What Would Need to Be True

ASC 606 does not require registrants to label or separately disclose every contract modification. However, the standard requires sufficient disclosure to enable users to understand the nature, amount, timing, and uncertainty of revenue and cash flows. A material change in commercial terms affecting loyalty economics would ordinarily be expected to be explainable through the ASC 606 disclosure framework, including disclosures about performance obligations, significant payment terms, contract balances, and significant judgements. Where such a change materially affects an interim period, a registrant would typically provide narrative explanation in its quarterly filing even if the Codification does not prescribe a discrete “contract modification” disclosure.

Why It Fails

The temporal sequence is inconsistent. The Q2 2025 anomaly occurred in April-June 2025. Alaska’s disclosed Bank of America contract amendments occurred in September 2025, and the Summit Visa Infinite card launched in August 2025, both subsequent to the anomaly quarter. Contractual modifications cannot retroactively cause accounting effects in prior quarters.

Moreover, the cash flow statement does not show unusual cash receipts in Q2 2025 that would correspond to a prepayment. The receivables increase of $195M represents the opposite of a prepayment, as it suggests amounts owed to Alaska rather than advance cash received.

GAAP Reference: ASC 606-10-50-12 requires disclosure of significant contract modifications.

Verdict: Contract restructuring is temporally impossible as disclosed amendments post-date the anomaly, and the cash flow pattern contradicts any prepayment hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: Breakage Assumption Refinement

The Benign Explanation

Airlines estimate the proportion of issued miles that will ultimately expire unredeemed (breakage). If Alaska reduced its breakage estimate in Q2 2025, expecting more miles to be redeemed, it would defer more revenue and increase the loyalty liability. An observer might suggest this explains the elevated issuance-to-revenue ratio.

What Would Need to Be True

Using management’s disclosed annual breakage sensitivity as a reference point, an illustrative back of the envelope analysis suggests that a very large change in breakage assumptions would be required to produce a liability movement of the magnitude observed in a single quarter. This estimate assumes a broadly linear relationship between breakage rate changes and liability impact, which may not hold precisely in practice. The conclusion is therefore directional: any such breakage revision would need to be unusually large relative to historical practice.

Why It Fails

ASC 250-10-50-4 explicitly requires disclosure of material changes in accounting estimates. No such disclosure appears. Alaska’s Q2 2025 10-Q makes no mention of breakage assumption changes. If a 15 percentage point breakage revision occurred without disclosure, that would itself be a GAAP violation.

Additionally, the single-quarter spike and immediate reversion pattern is inconsistent with a genuine breakage assumption change. If Alaska genuinely believed more miles would be redeemed, that belief would persist across quarters rather than appearing and disappearing within 90 days.

GAAP Reference: ASC 606 requires disclosures sufficient to enable users to understand the nature, amount, timing, and uncertainty of revenue and cash flows, including disclosure of significant judgements and explanations of material movements in contract balances. Material contract modifications would ordinarily be expected to be explainable within that disclosure framework and, where material to the interim period, discussed in the quarterly narrative.

Verdict: Breakage refinement fails the GAAP disclosure trap, as either no material change occurred (anomaly unexplained), or a material change occurred without disclosure (GAAP violation). The required magnitude is also economically implausible.

Hypothesis 5: Industry-Wide Disruption

The Benign Explanation

External factors such as changes in consumer credit card spending behaviour, macroeconomic shifts, or regulatory changes affecting frequent flyer programmes might have caused unusual patterns across the airline industry in Q2 2025. An observer might suggest Alaska is simply reflecting broader industry trends.

What Would Need to Be True

If industry-wide factors caused the anomaly, peer airlines would exhibit similar deviations from their historical patterns. United, Delta, and American, all operating large co-branded credit card programmes with similar structures, would show comparable ratio movements.

Why It Fails

Peer comparison demonstrates the anomaly is unique to Alaska.

United’s ratio was exactly at baseline. Delta showed only modest elevation. American was actually below its historical average. Whatever occurred at Alaska in Q2 2025 has no parallel at major US peers during the same period.

GAAP Reference: No specific provision; this is a factual test of whether the anomaly reflects company-specific versus industry-wide factors.

Verdict: Industry-wide disruption is empirically rejected. The anomaly is Alaska-specific.

Hypothesis 6: Summit Card Pre-Positioning

The Benign Explanation

Alaska launched its Summit Visa Infinite premium credit card in August 2025. An observer might suggest that Bank of America pre-purchased miles in Q2 2025 in anticipation of this launch, causing the issuance spike.

What Would Need to Be True

If Bank of America pre-positioned miles for Summit, the purchase would generate marketing revenue recognition under ASC 606. Marketing revenue, which is recognised immediately upon mile delivery, would show substantial year-on-year growth in Q2 2025.

Why It Fails

The decomposition of loyalty programme other revenue reveals that marketing and brand revenue grew only 4% year-on-year in Q2 2025, rising from approximately $135M to $140M. This modest growth is inconsistent with a substantial mile pre-purchase. The $181M excess issuance implied by the ratio anomaly vastly exceeds the $5M year-on-year growth in the marketing component.

Furthermore, the Summit card launched in Q3 2025, by which point the ratio had already normalised. If pre-positioning occurred, its effects would logically persist through the launch quarter rather than reversing before the card even became available.

GAAP Reference: ASC 606 requires revenue recognition when performance obligations are satisfied. Mile delivery triggers immediate marketing revenue recognition.

Verdict: Summit pre-positioning fails the marketing revenue test, as the relevant revenue line did not grow commensurately with the issuance spike.

Hypothesis 7: Receivable Timing and Cash Collection Lag

The Benign Explanation

Trade receivables fluctuate based on billing cycles and payment terms. An observer might suggest the $195M Q2 2025 receivables increase simply reflects timing of Bank of America payments, and that Q3 2025 saw normal cash collection.

What Would Need to Be True

If the receivables increase were genuine and subsequently collected, the Q3 2025 cash flow statement would show corresponding operating cash inflow. The receivables decline would be matched by cash receipts, and the asset would not need to be reclassified elsewhere on the balance sheet.

Why It Fails

The cash flow statement tells a different story. The Q2 2025 cash flow statement shows a use of operating cash of approximately $171M for accounts receivable movements, confirming the receivables spike was non-cash in nature. The Q2 2025 cash flow statement reflects a material operating cash outflow associated with accounts receivable movements, consistent with the receivables spike being largely non cash in nature. In Q3 2025, the reduction in reported receivables is not mirrored by an equally clear, isolated operating cash inflow attributable to collections. This pattern is consistent with some form of reclassification, netting, or offset within working capital rather than straightforward cash settlement, but the financial statements do not provide sufficient disaggregation to conclude definitively.

However, for a $129M receivable decline to reflect cash collection without being visible as a material operating cash tailwind, other working-capital items would need to show an equal-and-opposite outflow of comparable magnitude in the same quarter. A working-capital bridge can therefore falsify (or corroborate) this defence even without counterparty-level cash disclosure.

Instead of cash collection, approximately $120M appears to have been reclassified from current receivables to Other Noncurrent Assets, which rose from $316M to $436M between Q2 and Q3 2025. This reclassification received no explanatory disclosure.

GAAP Reference: ASC 210-10-45-1 governs balance sheet classification and requires assets to be classified based on their nature and expected realisation. Regulation S-K Item 303 requires MD&A disclosure of material changes in liquidity. If collectibility became uncertain or terms were modified in a manner that changes risk, the company would be expected to assess and reflect expected credit losses and describe the nature of the receivable/contract asset and collection assumptions.

Verdict: The cash flow data contradicts the timing explanation. The receivable was not collected; it was apparently reclassified without disclosure.

Hypothesis 8: Reclassification to Noncurrent Receivable Due to Extended Payment Terms

The Benign Explanation

Bank of America might have negotiated extended payment terms on a portion of its obligations to Alaska. An observer might suggest the movement from current receivables to noncurrent assets reflects a straightforward reclassification of the same receivable based on longer expected collection timing.

What Would Need to Be True

If Bank of America payment terms extended beyond one year, the receivable would remain a receivable, properly classified as noncurrent. ASC 606-10-45-3 is clear that a receivable is an unconditional right to consideration. If the right remains unconditional but simply has a longer collection horizon, it would be presented as a noncurrent receivable with appropriate disclosure. If a significant financing component exists due to the extended terms, ASC 606-10-32-15 requires either interest income or contra-revenue treatment. MD&A would address the liquidity implications of a major customer extending payment terms.

Why It Fails

The asset did not move to a “noncurrent receivables” line. It moved into the generic “Other Noncurrent Assets” category, which is not a receivable classification. There is no disclosure of modified Bank of America payment terms. There is no discussion of significant financing components or interest income. MD&A makes no mention of any impact on liquidity or working capital from modified partner payment terms.

For a movement of this magnitude, roughly $120M affecting a significant business relationship, silence in the financial statement notes and MD&A is inconsistent with standard disclosure practices.

GAAP Reference: ASC 606 distinguishes contract assets from receivables based on whether the entity’s right to consideration is conditional on something other than the passage of time. Where the entity has an unconditional right to consideration, the balance is presented as a receivable. Where consideration remains conditional on future performance or other factors, the balance is presented as a contract asset. Reclassification between these categories therefore reflects a change in the nature of the underlying right, not merely a balance sheet relabelling. As stated in the previous hypothesis, the company would be expected to assess and reflect expected credit losses and describe their nature.

Verdict: The “longer terms” explanation fails on classification (not presented as a receivable), financing treatment (no interest disclosed), and liquidity disclosure (no MD&A mention).

Hypothesis 9: Contract Asset Rather Than Receivable Relabelling

The Benign Explanation

ASC 606 distinguishes between receivables (unconditional rights) and contract assets (conditional rights, dependent on further performance). An observer might suggest the issue is merely one of labelling, that what Alaska calls a “receivable” is actually a contract asset, and the subsequent movement reflects proper reclassification.

What Would Need to Be True

If the amounts were truly contract assets, they would be presented and described as such under ASC 606-10-45-3. Note 3 (Revenue Recognition) would discuss contract asset balances, movements, and the nature of the conditionality. Any reclassification from receivable to contract asset would be explained, including what performance triggers must be satisfied.

Why It Fails

Alaska’s Q2 2025 10-Q explicitly presents “amounts due from affinity card partners and from other partners” as receivables, not contract assets. The presentation treats these as unconditional rights to consideration. In Q3 2025, the amounts do not appear in a contract asset line; instead, they apparently move into generic “Other Noncurrent Assets” with no contract asset disclosure.

There is no explanation of what conditionality or performance triggers would apply. The company treated these as receivables (unconditional), then moved a portion to an opaque balance sheet category without following ASC 606 contract asset disclosure requirements.

GAAP Reference: ASC 606-10-45-3 distinguishes receivables from contract assets based on conditionality. ASC 606-10-50-8 requires disclosure of contract balance explanations.

Verdict: This is not a mere labelling issue. The company treated these as receivables, then obscured part of them without following contract asset disclosure rules.

Hypothesis 10: Immaterial Presentation Differences

The Benign Explanation

Management characterised the $58M retroactive restatement of 2024 affinity receivables as “immaterial.” An observer might extrapolate this characterisation to the broader pattern, suggesting the entire Q2-Q3 2025 sequence represents nothing more than immaterial presentation adjustments not warranting detailed disclosure.

What Would Need to Be True

For the “immaterial” characterisation to hold across the full pattern, the amounts involved would need to be quantitatively and qualitatively immaterial under SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin 99 (SAB 99). SAB 99 establishes that materiality is not purely a numerical threshold; qualitative factors matter equally. An item is material if “there is a substantial likelihood that a reasonable investor would consider it important.”

Why It Fails

The quantitative test fails decisively. The estimated misstatement range of $120M to $200M represents 30% to 51% of Alaska’s 2024 net income of $395M. Even the most conservative estimate exceeds the commonly applied 5% threshold by a factor of six. The $58M restatement alone, at 15% of net income, strains any reasonable definition of immateriality.

Qualitative factors under SAB 99 are equally problematic. The anomaly masks a key revenue trend in Alaska’s third-largest revenue category. The reclassification distorts working capital and liquidity metrics used by investors. The pattern exhibits an exact temporal correlation with an extreme statistical outlier. The anomaly is unique to Alaska among peer airlines, suggesting company-specific factors rather than industry dynamics. The Bank of America relationship is explicitly described as a strategic asset in investor materials.

By any reasonable standard, these are not immaterial presentation differences.

GAAP Reference: SAB 99 sets forth qualitative factors for materiality assessment beyond numerical thresholds.

Verdict: “Presentation only” is not credible at these magnitudes. The amounts exceed standard materiality thresholds by 6-10x, and multiple SAB 99 qualitative factors are triggered.

Hypothesis 11: One-for-One Hawaiian Point Conversion Funded by Affinity Partner Economics

Benign Explanation

Following the Hawaiian Airlines acquisition, Alaska made a post-close commercial decision to convert HawaiianMiles into Alaska miles on a one-for-one basis. If HawaiianMiles historically carried lower standalone selling prices or lower expected fulfilment costs than Alaska miles, this conversion would increase the economic value of the outstanding loyalty obligation. Under this hypothesis, the Q2 2025 increase in loyalty contract liabilities reflects a cumulative catch-up to align the converted Hawaiian member population with Alaska programme economics. Rather than recognising the offset through a reduction in loyalty programme other revenue, Alaska recognised a receivable from its affinity card partner on the basis that the incremental obligation would be contractually funded by the partner over time.

What Would Need to Be True

The one-for-one conversion decision occurred post-close and was not an acquisition-date fact, such that the accounting impact properly falls under ASC 606 rather than ASC 805 purchase accounting.

The conversion materially increased the value of outstanding points, requiring recognition of an incremental loyalty contract liability via a change in estimate or contract modification analysis.

The affinity card agreement includes provisions that obligate the partner to fund the increased value of previously issued points, giving Alaska a present and enforceable right to incremental consideration.

The recognised balance qualifies as a receivable rather than a contract asset, meaning the right to consideration is unconditional or conditional only on the passage of time.

Any portion expected to be collected beyond twelve months is appropriately classified as non-current with clear disclosure of settlement terms.

Why It Likely Fails

This hypothesis requires a combination of a post-close economic upgrade and a contractual repricing of the affinity relationship, neither of which is described in the public filings. The filings do not disclose a material change in loyalty programme economics, a repricing or true-up mechanism with the affinity partner, or a renegotiation of partner funding terms. The subsequent reclassification of the balance into a generic “Other Non-Current Assets” line item, rather than a clearly identified receivable or contract asset with disclosed terms, is inconsistent with how material, enforceable partner claims are typically presented.

GAAP Reference: ASC 606 requires receivables to reflect unconditional rights to consideration and contract assets to reflect rights conditional on future performance or events. Material changes in revenue recognition judgements or contract balances are expected to be explainable through disclosure. Post-acquisition changes in loyalty economics do not adjust goodwill and are accounted for through revenue recognition mechanics rather than purchase accounting.

Verdict: A one-for-one conversion can explain an increase in loyalty contract liabilities in principle. It does not naturally explain recognition of a large affinity receivable unless the partner is contractually obligated to fund the incremental value. Absent disclosure of such contractual mechanisms, this hypothesis remains incomplete.

Hypothesis 12: Single Loyalty Platform Migration Revaluation of Acquired Mileage Liabilities

Benign Explanation

The Q2 2025 anomaly reflects a non-cash technical remeasurement when HawaiianMiles balances were migrated onto Alaska’s loyalty platform and subledger. HawaiianMiles points were historically measured using Hawaiian’s assumptions. Upon migration, Alaska aligned the acquired outstanding miles to Alaska’s higher SSP and redemption cost assumptions, producing a one-time increase in the loyalty contract liability without corresponding revenue.

What Would Need to Be True

The migration occurred in Q2 2025 and required formal alignment of valuation and recognition policies.

HawaiianMiles liabilities were carried under materially different assumptions that, when aligned, increased the measured obligation.

The adjustment reflects either acquisition-date facts finalised within the ASC 805 measurement period or a post-close change in estimate under ASC 606.

If ASC 805 applies, goodwill would increase. If ASC 606 applies, a cumulative catch-up to revenue would occur.

The migration explains a discrete step change rather than a gradual trend.

Why It Likely Fails

If the adjustment were an ASC 805 measurement period update, goodwill would be affected and disclosed as such. If it were an ASC 606 change in estimate, a visible revenue impact would be expected. The filings show neither a material goodwill adjustment nor a commensurate revenue catch-up, and provide no narrative explaining a migration-driven revaluation of this magnitude.

GAAP Reference: ASC 805 measurement period adjustments adjust goodwill for acquisition-date facts. ASC 606 changes in estimates affecting loyalty obligations require cumulative catch-up accounting through revenue unless funded by a third party.

Verdict: A platform migration can trigger a liability remeasurement, but the accounting must resolve through either goodwill or revenue. The absence of either outcome weakens this explanation.

Hypothesis 13: Long-Term Affinity Partner Financing Structure

Benign Explanation

The Q2 2025 spike in receivables reflects recognition of a claim against the affinity card partner to fund integration-related loyalty costs, with the Q3 reclassification to non-current assets reflecting formalisation of a long-term settlement schedule extending beyond twelve months.

What Would Need to Be True

The affinity agreement includes enforceable provisions requiring the partner to fund integration or loyalty harmonisation costs.

Alaska has an unconditional or time-only conditional right to the consideration.

The timing of expected cash flows supports non-current classification.

Any significant financing component is appropriately considered and disclosed.

The arrangement is sufficiently material to warrant explanation.

Why It Likely Fails

The filings do not describe a material renegotiation or repricing of the affinity agreement, nor do they clearly present the balance as a non-current receivable or contract asset with disclosed terms. Presentation within a generic non-current asset category obscures the nature of the claim and is inconsistent with standard practice for material partner financing arrangements.

GAAP Reference: ASC 606 distinguishes receivables from contract assets based on unconditional rights to consideration. Material partner arrangements and long-dated settlement terms are expected to be disclosed.

Verdict: A long-term partner funding arrangement could explain the classification change, but the absence of disclosure and clear presentation materially undermines this hypothesis.

Hypothesis 14: Post-Migration Redemption Surge from Newly Enabled Partner Access

Benign Explanation

The elevated partner redemption costs reflect legitimate pent-up demand by Hawaiian members gaining access to Alaska’s broader partner network following platform integration, rather than fraud or cybersecurity failures.

What Would Need to Be True

Platform integration materially expanded partner redemption options.

Hawaiian members redeemed at higher-value partners at elevated rates.

Redemption mix shifted materially toward higher-cost partners.

Customer complaints reflect migration friction rather than account compromise.

Why It Likely Fails

While this hypothesis plausibly explains increased redemption costs and customer noise, it does not explain a discrete, large increase in loyalty contract liabilities. A redemption surge reduces liabilities rather than creates them, unless paired with a separate liability revaluation event that is not clearly disclosed.

GAAP Reference: Under ASC 606, redemptions reduce contract liabilities and trigger cost recognition. Redemption activity alone does not increase deferred revenue.

Verdict: Redemption surges explain cost pressure and customer disruption, but not the observed liability issuance anomaly in isolation.

Hypothesis 15: Measurement Period Adjustments Under ASC 805

Benign Explanation

The $58 million retroactive adjustment reflects a standard ASC 805 measurement period refinement to acquired balances, such as legacy Hawaiian receivables, and is not indicative of error or irregularity.

What Would Need to Be True

The adjustment relates to acquisition-date facts.

It falls within the one-year measurement period.

The adjustment affects goodwill rather than current-period earnings.

The nature of the adjustment is described in the purchase accounting disclosures.

Why It Likely Fails

Measurement period adjustments can explain retrospective changes, but they do not explain a Q2 2025 loyalty issuance-to-revenue ratio spike unless the spike itself reflects a purchase accounting adjustment. The filings indicate no material measurement period adjustments to the loyalty obligation, limiting the explanatory power of this hypothesis.

GAAP Reference: ASC 805 permits retrospective adjustment of provisional amounts for acquisition-date facts, with corresponding goodwill adjustments.

Verdict: Measurement period accounting can explain discrete retrospective changes, but it does not plausibly explain the full Q2–Q3 2025 pattern observed.

Hypothesis 16: Mass Reinstatements / Customer Make‑Goods (Issuance Without Consideration)

The Benign Explanation

Alaska reinstated large volumes of previously issued miles (or granted customer make‑good credits) due to account compromise, operational correction, or migration issues. This would increase “liability for loyalty points issued” without increasing “loyalty programme other revenue.”

What Would Need to Be True

The reinstated/credited miles were recorded as an increase to the loyalty contract liability in Q2 2025.

The offset was recorded as (i) an operating expense (customer service/fraud), or (ii) contra‑revenue within passenger or loyalty revenue, or (iii) another clearly identifiable income statement line.

The scale would be reconcilable to a discrete event and explain the reversion in Q3.

If driven by cyber compromise, risk/incident disclosure would be expected to align with the magnitude of customer restitution.

Why It Fails

Public disclosures do not identify a discrete income statement line item consistent with a customer restitution event of the magnitude implied by the $180M “excess” liability creation, nor do they provide a quantified rollforward that isolates reinstatements/adjustments versus partner‑funded issuances.

GAAP Reference: ASC 606 requires contract liability movements to be explainable through contract balance disclosures; material changes in judgements and material movements that affect revenue timing should be understandable from disclosures.

Verdict: Reinstatements can explain the direction of the ratio move but fail the disclosure and reconciliation test absent quantified rollforwards and identifiable offsets.

Hypothesis 17: Revenue Caption Reclassification (Denominator Shift)

The Benign Explanation

The observed issuance-to-revenue ratio spike is not driven by changes in loyalty issuance economics, but by a temporary reclassification of loyalty-related revenue between “Loyalty programme other revenue” and other revenue captions (for example passenger revenue or marketing revenue). Under this explanation, the denominator of the ratio was understated in Q2 2025 due to presentation choices rather than economic change.

What Would Need to Be True

For this explanation to hold, the following conditions would need to be met:

Alaska reclassified a material portion of loyalty-related consideration away from “Loyalty programme other revenue” in Q2 2025.

The reclassification affected only the presentation of revenue, not total revenue, and therefore did not trigger changes in cash flow.

Comparative periods were either recast, or the reclassification was disclosed clearly enough for investors to understand period-to-period comparability.

The reclassification reversed or normalised in Q3 2025, coinciding with the ratio’s reversion to baseline.

Why It Fails

No disclosure in the Q2 2025 or Q3 2025 filings describes any reclassification of loyalty-related revenue captions. There is no footnote explaining a change in revenue presentation, no recast of prior-period comparatives, and no MD&A discussion of revenue classification changes affecting trend analysis.

Absent disclosure, investors have no basis to conclude that the ratio spike reflects a denominator artefact rather than a genuine economic or accounting event. Moreover, a reclassification large enough to produce a 10.40σ deviation would be qualitatively material under SAB 99 and would ordinarily be disclosed even if total revenue were unchanged.

GAAP Reference: ASC 606-10-50 and Regulation S-K Item 303 require disclosure sufficient to enable users to understand the nature and comparability of revenue streams. Material changes in revenue presentation that affect trend analysis require explanation.