ALK Accounted Addendum

THE GAME IS UP: AN ASTONISHING FOUR-YEAR COVER UP AT ALK 0.00%↑

January 2026

Addendum to the previous Baked Alaska report.

A summary of the overall investigation can be found here.

DISCLAIMER: The author holds a short position in Alaska Air Group (ALK) and stands to profit from a decline in the share price. This supplementary addendum should be read in conjunction with the main report dated 9TH January 2026. It represents analysis of publicly available information and constitutes opinion, not investment advice.

The Four Year Old Policy That Demonstrates a Four Year Old Concealment

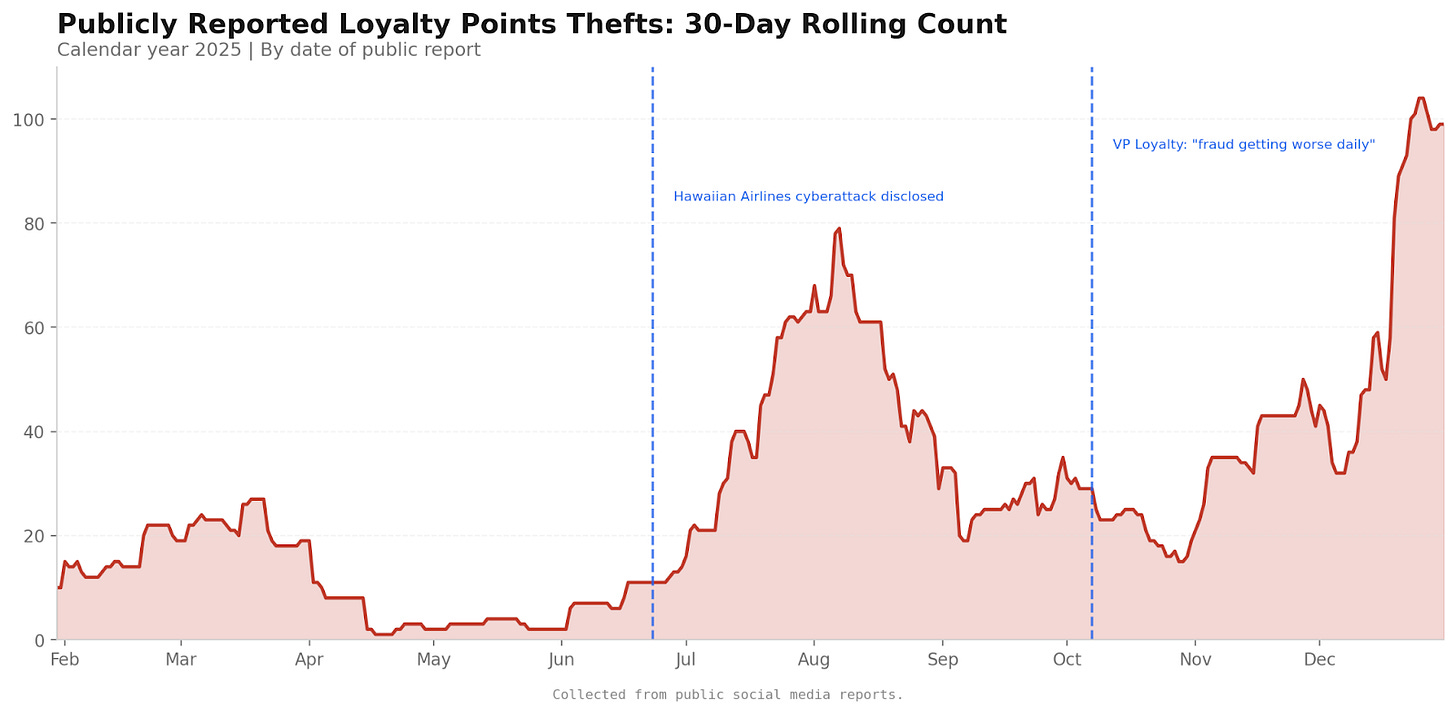

On the 9th January 2026, the Nosey Parker released a forensic report that documented 370 account thefts and a 10.40σ accounting anomaly. It posed questions for management.

The main report documented 370 account thefts and a 10.40σ accounting anomaly. It posed questions for management.

This addendum answers them.

Two facts, taken together, permit only one conclusion.

Fact One

The method of account theft in 2022 is identical to the method in 2025:

Last-minute partner airline bookings in names unassociated with the account

Notification email changed to prevent victim awareness

Alaska could not detect or prevent these thefts in 2022. It cannot detect or prevent them today. The vulnerability is unchanged in 45 months.

Fact Two

Every documented victim receives the same remediation:

Points restored as a “one-time courtesy”

Victim blamed for password compromise

Account permanently restricted to telephone-only award booking via PIN unlock

This protocol is universal. It has been applied since at least April 2022.

The Question

Why would Alaska permanently restrict a victim’s account after the compromised password has been changed?

If password compromise were the vulnerability, a new password would resolve it. Alaska could require a 24-character password, mandate monthly rotation, and add security questions. Any of these would address a password-based attack while preserving online access. No matter the loss in confidence of the customer’s password hygiene.

Instead, Alaska removes online booking capability entirely. Permanently.

The Answer

Alaska cannot determine whether any given account was compromised via password or via session hijacking.

Session tokens persist after password changes. If an attacker obtained a victim’s session token, changing the password does nothing. The attacker can return and drain the restored points using the same token.

The only defence Alaska’s architecture permits is disconnection. Remove the account from the online system entirely. Force all award bookings through a telephone channel that bypasses the vulnerable session infrastructure.

The PIN-lock is not a security enhancement. It is an admission that the platform cannot be secured.

The Concealment

Alaska tells victims their password was compromised. This framing serves three purposes:

It assigns fault to the victim

It makes the PIN-lock appear reasonable rather than extraordinary

It prevents the victim from understanding that Alaska owes them a fix, not a courtesy

For 45 months, Alaska has applied this protocol. For 45 months, Alaska has known the vulnerability extends beyond passwords. For 45 months, Alaska has blamed users rather than disclose an architectural failure it cannot remediate.

What Follows

The remainder of this addendum examines:

Part I: The technical architecture that makes session-level attacks possible and remediation impossible

Part II: The stakeholders who cannot be told, and the consequences if they were

Part III: The six months of IT failures and non-disclosure in H2 2025

Part IV: The liability measurement problem created by victim-dependent detection

Part V: The material weakness determinations that follow from documented facts

Part VI: The regulatory and operational consequences now inevitable

Part I: The Legacy Architecture Problem

Airlines operate on reservation systems developed in the 1960s - mainframe architectures designed before the internet existed. Modern web and mobile interfaces must translate between customer expectations and these legacy backends.

This creates structural vulnerabilities. Session management, real-time fraud detection, and authentication protocols must be grafted onto systems never designed to support them. The integration is fragile. Upgrades are expensive, time-consuming, and carry operational risk.

The major US carriers recognised this and invested accordingly. American, Delta, and United implemented two-factor authentication by 2024. The 23× theft rate documented in the main report reflects Alaska’s failure to do likewise.

But two-factor authentication alone would not solve Alaska’s problem. 2FA protects the authentication moment - the initial login. It does not protect against session hijacking after authentication, nor does it provide real-time visibility into anomalous redemption patterns. Alaska’s architecture appears blind to both.

How Session Hijacking Works

When a user logs into Alaska’s website, the system creates a session token stored as a browser cookie. This token tells Alaska’s servers: “This browser belongs to an authenticated user. Do not require them to log in again.”

Session tokens are designed for convenience. They persist for hours, days, or until explicitly cleared. They allow users to close their browser, return later, and resume activity without re-entering credentials.

The vulnerability arises because session tokens are bearer instruments. Whoever possesses the token is treated as the authenticated user. If an attacker obtains a valid session token, they gain full account access without ever knowing the password.

Why Password Changes Do Not Help

Changing a password protects against future password-based attacks. It does nothing to invalidate existing session tokens.

Consider the sequence:

User logs in, creating session token A

Attacker steals session token A through malware, compromised WiFi, or platform breach

User discovers unauthorised activity and changes password

Session token A remains valid because password changes do not automatically terminate existing sessions

Attacker continues accessing the account using session token A

This explains the otherwise inexplicable pattern documented across victim accounts: users who changed their passwords immediately after discovering fraud, only to be compromised again within hours.

The Architectural Constraint

A modern platform would address this through session invalidation. Upon password change or security incident, all existing sessions are terminated. The user must re-authenticate on every device.

This requires the platform to maintain a centralised session registry with real-time invalidation capability. Legacy architectures lack this infrastructure. Sessions are validated locally against token expiry timestamps, not against a central authority that can revoke them.

The alternative is wholesale session termination for all users. This is operationally disruptive and would require explanation. For Alaska, it would also draw attention to the underlying vulnerability.

The PIN-lock protocol is Alaska’s workaround. Rather than fix session management, they disconnect compromised accounts from the online booking system entirely. The telephone-and-PIN process creates a new authentication pathway that bypasses the vulnerable web session infrastructure.

This is not a security enhancement. It is an admission that the existing session architecture cannot be secured.

The AwardWallet Contrast

The third-party service AwardWallet demonstrates that real-time account monitoring is technically feasible. AwardWallet notifies users instantly when loyalty account details change, regardless of whether the notification email has been modified.

This investigation understands that the technical wizardry at AwardWallet is… it logs into your account frequently, and alerts you if your balance has changed.,

Alaska has deigned not to implemented any such workaround, despite being custodian of the whole system. The reason is now apparent: doing so would alert victims in real-time, creating documentation of breach scale that Alaska currently suppresses by relying on delayed self-discovery.

Temporal Scope

The earliest documented incident with the characteristic PIN-lock protocol is April 2022, establishing 45 months of continuous vulnerability. However, victim testimony suggests the breach may be older:

“I went through it, but it was maybe 5-6 years ago. I did get my miles reinstated. Then I had to set a pin that I would have to call AS and provide anytime I wanted to book an award flight which would unlock my account for 5-10 minutes.”

This account is too vague to rely upon definitively, but it indicates the PIN-lock protocol may have been in place since 2018 or 2019 - extending the breach window to potentially seven years.

Part II: Maintaining the Charade

Customers Cannot Be Told

The truth would trigger immediate remediation demands and mass account closures.

If Alaska disclosed that the platform vulnerability is architectural rather than user-caused, every PIN-locked victim would understand they were deceived. The “one-time courtesy” framing would collapse. Class action exposure would crystallise overnight.

More critically, disclosure would trigger a redemption surge. Members who understood their balances were held in an indefensible system would rush to extract value before catastrophic loss. The $3.4 billion deferred revenue balance would face liquidity pressure Alaska cannot absorb.

The lie serves a dual function: it suppresses individual claims and prevents collective action.

Auditors Cannot Be Told

The control environment is incompatible with a clean SOX 404 opinion.

Effective internal control over the loyalty programme requires that Alaska can distinguish legitimate from fraudulent redemptions. The PIN-lock protocol proves it cannot. Fraudulent redemptions are detected only when victims complain, days or months after the transaction. Until complaint, the redemption is recorded as legitimate. The liability balance contains an unknowable error term.

This is not a control deficiency. It is control absence. The redemption population includes an unmeasured quantity of fraud that Alaska can neither prevent, detect, nor quantify until victims self-report.

If KPMG understood that Alaska’s fraud detection mechanism is victim complaint, the audit conclusion would necessarily change. Management’s representation that controls are effective cannot be reconciled with a platform that relies on customers to identify theft.

Partner Airlines Cannot Be Told

Qatar Airways and other oneworld partners are reimbursed for award travel at contractual rates. They have no visibility into whether redemptions were legitimate bookings or organised theft. If partners understood the exposure, renegotiation would follow. Whether partners have noticed anomalies is unknown.

Investors Cannot Be Told

The disclosure would be self-executing destruction.

The moment Alaska acknowledges a multi-year platform vulnerability enabling systematic theft, the following cascade becomes inevitable:

Restatement of loyalty programme liabilities with unknowable error margin

Material weakness determination under SOX 404

Auditor qualification or resignation

Covenant compliance review by lenders

Credit rating agency reassessment

Securities litigation class period crystallisation

Management credibility collapse

The $180 million excess loyalty liability creation documented in the main report may represent the financial signature of this concealment. If Alaska restored millions of stolen miles while blaming victims for password failures, the accounting impact would appear as liability issuance without corresponding revenue. The Q2 2025 anomaly is precisely this pattern.

Every quarter of concealment increases the eventual liability. The Hawaiian merger added merger securities fraud exposure. The Accenture statements locked management into representations contradicted by evidence.

The strategy is therefore not disclosure avoidance but disclosure deferral. Management appears to be betting that the vulnerability can be remediated before external discovery forces acknowledgment.

Law Enforcement Cannot Be Told

The concealment strategy extends to law enforcement. You see the rage burn at victims who see refusal and even obstruction of law enforcement involvement.

Ambivalence: “I asked if I should report to authorities and she told me not to even bother.”

Inaction by Policy: A $12k value ticket discovered prior to US departure “[When I asked what Alaska was] going to do to hold the person accountable I was told that they had canceled the flight and no further action would be taken.”

Active Obstruction: “I tried contacting customer service to get the passenger’s specific information [to try to get arrested] but they said they couldn’t disclose it due to privacy concerns.”

The Houston Inbound case documented in Appendix A demonstrates the pattern at its most acute: a victim notified Alaska while the fraudulent passenger was in transit to the United States, hours before landing. Alaska’s response: “There was nothing they could do.”

The Consequence of Non-Cooperation

Law enforcement involvement would accomplish two things Alaska evidently wishes to avoid:

Documentation: Formal reports would create a record of incident volume that Alaska currently controls

Deterrence: Arrests would reduce demand for fraudulently obtained tickets

By refusing cooperation, Alaska ensures no external record of breach scale exists and that the criminal enterprise continues unimpeded. The thieves face no consequences. The market for stolen miles persists.

Alaska’s non-cooperation has enabled organised crime to operate continuously for years. The criminals face no law enforcement risk. The theft market persists.

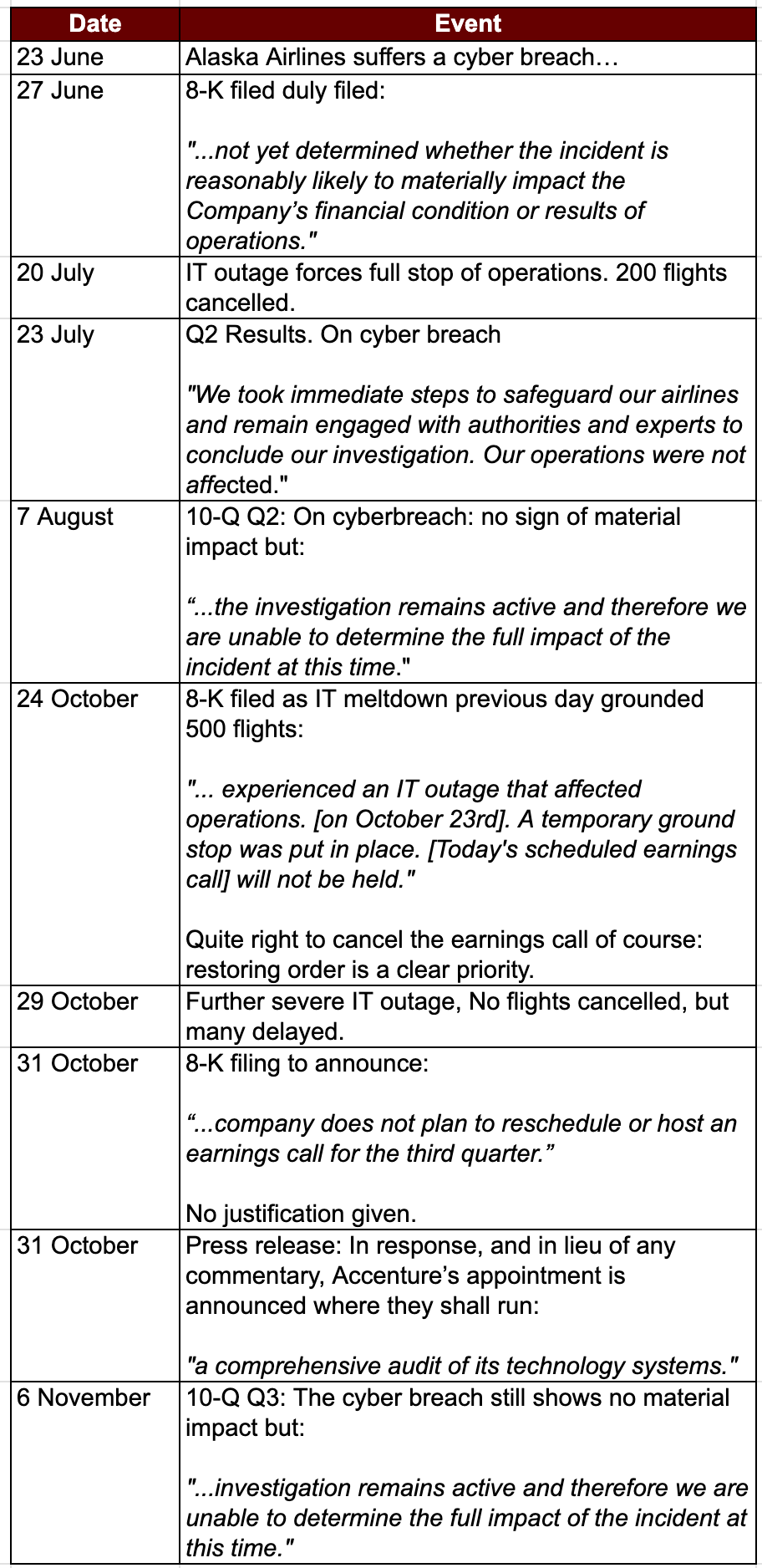

Part III: Six Months in IT at Alaska Airlines in H2 2025

The Scattered Spider Attribution

The June 2025 breach was part of a coordinated Scattered Spider campaign against airlines.

Scattered Spider is an organised crime collective considered as sophisticated as some nation-state actors. The group was responsible for the 2023 MGM Resorts and Caesars Entertainment breaches that cost over $100 million combined.

In July 2025, multiple cybersecurity firms publicly attributed the airline attacks. Toby Lewis, global head of threat analysis at Darktrace, stated that the breaches bore “the hallmarks of Scattered Spider, the same group behind recent attacks on Hawaiian Airlines, WestJet, and Marks & Spencer.” Mandiant’s CTO Charles Carmakal confirmed awareness of “multiple incidents in the airline and transportation sector which resemble the operations of UNC3944 or Scattered Spider.” The FBI issued a formal alert on 1 July 2025 confirming that “Scattered Spider [is] expanding its targeting to include the airline sector.”

Hawaiian Airlines, now an Alaska subsidiary, was explicitly named as a Scattered Spider victim.

Qantas disclosed promptly: 6 million member accounts, ransom demands received, executive remuneration reduced as accountability. WestJet disclosed in October.

Alaska has disclosed nothing beyond boilerplate. Not the attacker. Not the scope. Not the accounts affected. Seven months later, the investigation “remains active” and Alaska is “unable to determine the full impact.”

The implicit message to investors: Scattered Spider breached Hawaiian Airlines, WestJet, and Qantas, but Alaska’s systems resisted. This strains credulity. Hawaiian is an Alaska subsidiary. Though they breached the outer walls of ALK, once inside, they came up against an opponent with even greater levels of sophistication and Scattered Spider could only come away knowing they were beaten by a more sophisticated technical operation?

The CISA advisory on Scattered Spider notes that one of the group’s documented attack vectors is “Steal Web Session Cookie(s).” This is precisely the vulnerability that explains the PIN-lock protocol and the pattern of repeat compromise documented throughout this report.

Alaska Airlines could not have been less forthcoming over this six month trail of IT hardship.

A Historical Allergy to Disclosure

Alaska’s reticence on the cyber breach is consistent with a broader pattern of disclosure minimisation.

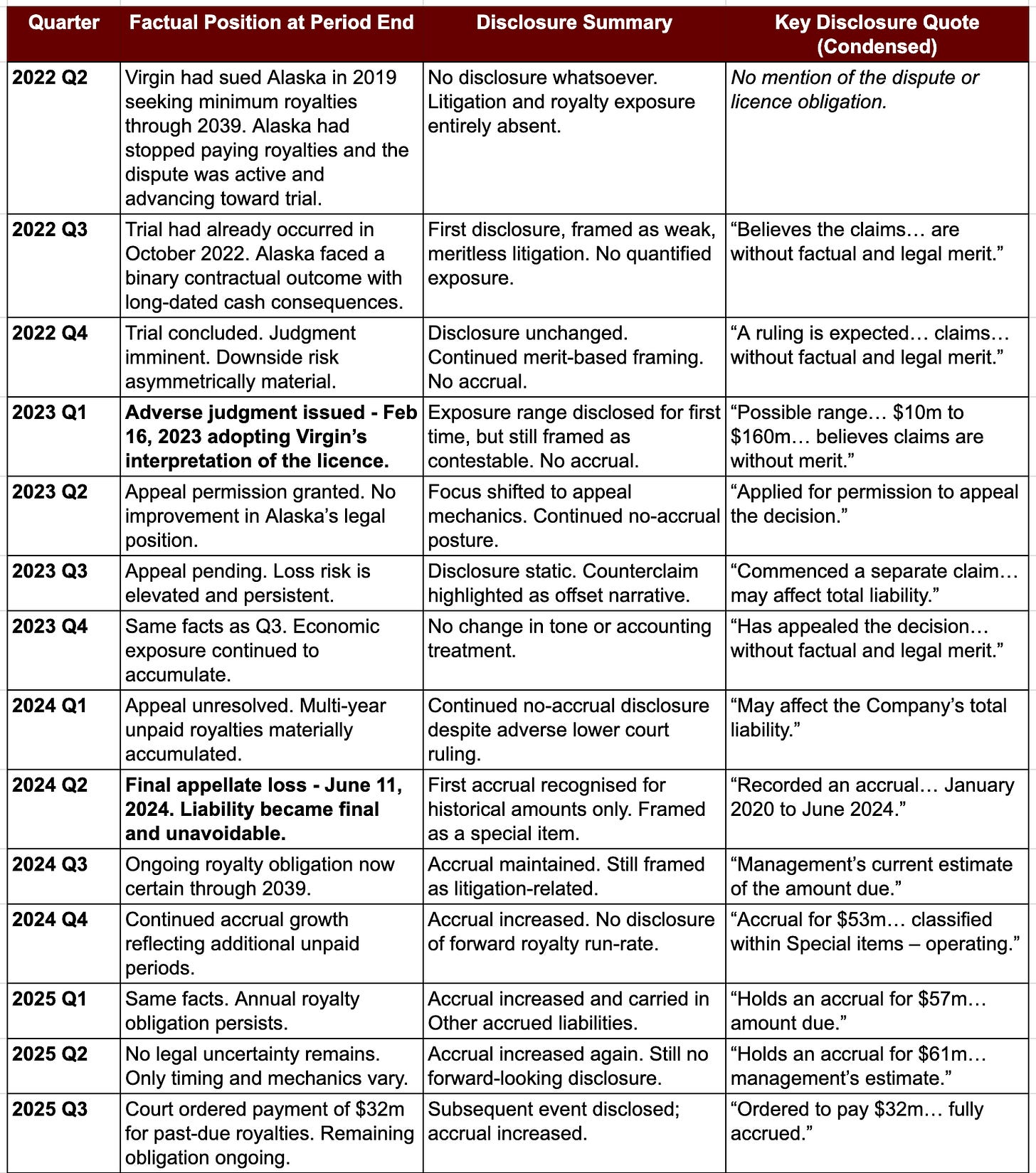

Appendix B documents Alaska’s handling of the Virgin America trademark litigation, a dispute that ultimately required Alaska to pay approximately $200 million in royalties through 2039. The disclosure trajectory is instructive:

The lawsuit was filed in 2019. Alaska made no disclosure whatsoever until Q3 2022, after trial had already occurred.

The first disclosure dismissed the claims as “without factual and legal merit.”

That phrase was repeated verbatim for five consecutive quarters, even after an adverse judgment was issued in February 2023.

Alaska recorded no accrual until the final appellate loss in June 2024, despite an adverse lower court ruling sixteen months earlier.

Even after liability became certain, disclosures quantified only past-due amounts, never the remaining fifteen-year royalty obligation.

The result was not a GAAP violation. It was something more subtle: systematic minimisation of certainty, duration, and magnitude through careful wording rather than misstatement. Investors reading Alaska’s disclosures quarter by quarter would have consistently underestimated the probability and scale of the eventual liability.

The cyber breach disclosures follow the same pattern. Seven months of “investigation remains active” and “unable to determine the full impact” is not transparency. It is managed ambiguity designed to avoid definitive statement until definitive statement becomes unavoidable.

The Accenture Audit

On 31 October 2025, Alaska announced it had engaged Accenture to conduct “a comprehensive audit of its technology systems” including “a top-to-bottom review of Alaska’s technology environment, assessing standards, processes, and overall system health.”

The scope was explicitly broad. The repetition of guest-centered and guest-facing systems under review appeared explicit.

On 4 December, CFO Shane Tackett summarised Accenture’s preliminary findings at the Goldman Sachs Industrials Conference:

No connection with the Hawaiian merger

The outages reflected an abundance of “:innovation” stretching system limits

The incidents were isolated, not systemic

Remediation requires only “a little more redundancy at relatively low cost”

“We don’t have a systemic architecture failure in our data or infrastructure”

This is a comprehensive exoneration. Tackett attributed the conclusions to Accenture, not to management’s own assessment.

These statements cannot be reconciled with a platform that:

Cannot detect anomalous redemption patterns

Cannot verify email changes before execution

Cannot prevent repeat compromise without removing accounts entirely

Requires permanent telephone-only access for theft victims

Either Accenture’s “top-to-bottom review” did not examine the loyalty programme despite it being a guest-facing system, or Accenture examined it and reached conclusions contradicted by documented evidence.

Neither interpretation supports confidence in Alaska’s technology governance. And Tackett’s unqualified reliance on Accenture’s preliminary findings, delivered publicly to institutional investors, creates additional exposure if those findings prove incomplete.

Part IV: The Liability Problem

Detection Depends on Victims

The vast majority of documented victims discovered the theft themselves, logging into their account days, weeks, or months after the fact.

This means Alaska has no independent visibility into:

How many accounts have been compromised

How many miles have been fraudulently redeemed

When fraudulent redemptions occurred

The $45 million of elevated partner redemptions in Q2 and Q3 2025 documented in the main report occurs within this context. A benign explanation is possible: customer behaviour may have shifted toward partner redemptions. There is no commercially striking imperative that would suggest that.

But the timing coincides precisely with the documented acceleration in theft reports. Management cannot distinguish between the two because it has no independent visibility into fraudulent redemptions.

The Accounting Consequences

The $3.4 billion deferred revenue balance represents miles issued but not yet redeemed. When miles are redeemed, the liability is reduced. When miles are fraudulently redeemed but Alaska is unaware, the liability is understated. When victims eventually report and miles are restored, new liability is created.

Though the quantum of thefts remains unknown, we can say that without doubt, that the deferred revenue balance can not be reliably known by ALK, if they do not reliably know how many members accounts have been stolen from, and how many loyalty points they must replenish and add to the deferred revenue balance.

The combined $45 million of elevated partner redemptions versus trend could be entirely fraudulent flights, and ALK would have no way of knowing other ways.

This is a loyalty programme without functioning controls, and a liability balance that is unknowable by ALK. Lest we forget the fraud expenses suffered, but yet to be discovered by their victims, ALK’s members.

Part V: Material Weakness Determinations

Under PCAOB Auditing Standard No. 2201, a material weakness is:

“A deficiency, or a combination of deficiencies, in internal control over financial reporting, such that there is a reasonable possibility that a material misstatement of the company’s annual or interim financial statements will not be prevented or detected on a timely basis.”

The following material weaknesses exist:

Preventive Controls Over Loyalty Redemptions No effective controls prevent high-risk redemptions. Fraudulent transactions are not prevented.

Detective Controls and Fraud Monitoring Detection depends on victim self-reporting. Fraudulent activity is not detected on a timely basis.

Notification Integrity Email address changes execute without verification, eliminating the primary detective mechanism.

Disclosure Controls Known multi-year risks were not disclosed. The 23 June incident remains unresolved after seven months with contradictory materiality assertions.

Management Override PIN locks substitute customer penalty for system remediation, obscuring the control failure.

Part VI: The Sanguinary Consequences

For at least 45 months - and possibly as long as seven years - Alaska Air Group has known of a platform vulnerability beyond compromised passwords. Management’s response was not to fix the system but to conceal its existence: blaming victims in the cause of concealment, restricting their accounts, refusing law enforcement cooperation, and disclosing nothing to investors or regulators.

This strategy enabled organised crime to operate continuously. Fraudulent tickets were sold. Partner airline cabins were occupied by criminals. Foreign nationals entered the United States on proceeds of theft. Alaska’s concealment facilitated all of it.

The PIN lock is not a security measure. It is an admission. The only reason to permanently disconnect an account from the online platform is because the platform cannot be secured. Management knows this. The PIN lock proves it.

A $3.4 billion deferred revenue balance operates without controls to verify its completeness.

A $12 billion loyalty programme (ALK’s valuation as per December 2024) lacks basic fraud detection. And an “ongoing investigation” into a breach by one of the world’s most sophisticated criminal groups has produced seven months of silence.

This is not a customer error. This is not an IT failure.

This is systemic concealment of a material business risk.

The scope of consequences is enormous.

Audit Failure

KPMG signed clean opinions on internal controls whilst a multi-year fraud mechanism operated undetected. The SOX 404 certifications state that management maintains effective internal control over financial reporting. This statement cannot be reconciled with a loyalty platform that cannot prevent, detect, or accurately measure fraudulent redemptions.

Either KPMG was not informed of the breach scale and victim remediation protocols, or audit procedures failed to identify the pattern. Both outcomes are damning. PCAOB will initiate a targeted inspection of KPMG’s audits for fiscal years 2022-2025, focusing on evaluation of management’s assessment of internal controls, testing of key controls over loyalty programme accounting, and evaluation of fraud risk factors and responses.

Operational Crisis

Upon public disclosure, Alaska faces immediate operational pressure: social media crisis, news cycle domination, member backlash, corporate travel policy exclusions, reduced forward bookings. Load factors decline. Yield collapses as distressed inventory floods the market.

The $3.4 billion deferred revenue balance faces crystallisation risk. Members demand cash equivalent redemptions. Partners demand immediate settlement. Lenders invoke covenant breaches. Vendors require cash on delivery terms. A liquidity crisis develops that cannot be managed through operating cash flow.

Regulatory Nightmare

The documented facts trigger mandatory investigations across multiple federal agencies, each with distinct jurisdictional hooks:

SEC Division of Enforcement will assess material omissions in periodic filings, adequacy of internal controls over loyalty programme accounting, accuracy of management certifications under SOX 302 and 404, and timeliness of 8-K disclosures regarding the Hawaiian Airlines breach.

Department of Justice: Criminal Division will evaluate whether concealment constitutes wire fraud, securities fraud, false statements, or obstruction.

Department of Homeland Security (CBP, ICE, TSA) will assess whether Alaska’s non-cooperation policy constitutes facilitation of illegal entry, given documented instances where Alaska had advance notice and passenger identification of fraudulent international travel to US ports of entry.

FBI will investigate the theft operation as an organised criminal enterprise, assessing whether Alaska’s systematic refusal to cooperate with law enforcement enabled the ongoing criminal activity.

State Attorneys General, beginning with Washington and Alaska, will pursue investigations under consumer protection statutes, with the Alaska AG having already formally complained about institutional non-cooperation with law enforcement.

These investigations are not independent. SEC referrals trigger DOJ assessment. State AG coordination amplifies enforcement leverage. Each proceeding generates discovery that feeds the others.

The question is not whether these consequences materialise. The question is sequence and timing.

This report terminates the concealment strategy. What follows is arithmetic.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tommy Caton was co-founder, Chief Revenue Officer, and Chief Financial Officer of travel data analytics firm AirDNA from 2015 to 2022. He holds an MBA in finance from the Kellogg School of Management (Northwestern University) and worked for four years in KPMG’s Corporate Finance division.

The author is not a professional short seller. This analysis originated from noticing irregularities in publicly available information, which led to taking a short position in Alaska Air Group. Aside from this stock, 100% of investable assets are in diversified funds. However, that does make me a short-seller. Weigh that up, as you weigh up my words.

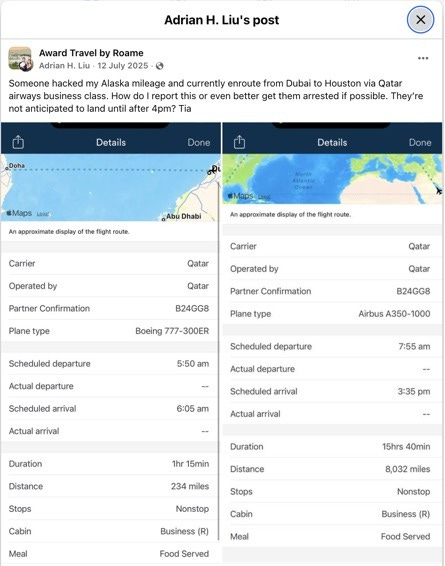

Appendix A: The Houston Inbound Case

Key Facts

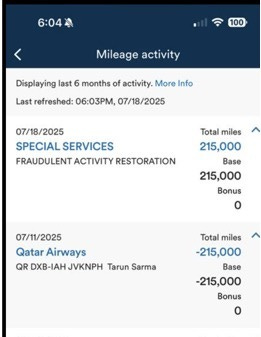

Date of Discovery: 12 July 2025

Route: Dubai to Houston via Doha (Qatar Airways)

Cabin: Business Class

Miles Stolen: 215,000

Fraudulent Passenger Name: Visible in booking records (see screenshots)

US Port of Entry: Houston George Bush Intercontinental Airport

Notification Window: Multiple hours before scheduled 4pm landing

Law Enforcement Coordination: None (per victim account)

Screenshot 1: Victim’s Initial Report

The victim posted to the Facebook group “Award Travel by Roame” on 12 July 2025, showing the fraudulent booking details and asking how to report the fraud or have the person arrested.

Victim’s statement: “Someone hacked my Alaska mileage and currently enroute from Dubai to Houston via Qatar airways business class. How do I report this or even better get them arrested if possible. They’re not anticipated to land until after 4pm.”

Source: Facebook, Award Travel by Roame group. Archive: archive.ph/IVxmB

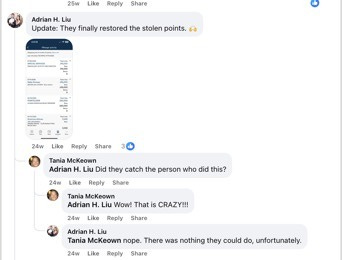

Screenshot 2: Customer Service Response and Booking Record

The victim’s update shows: Alaska Airlines customer service mentioning the compromise may be linked to a recent data transfer issue, suggesting awareness of a broader security problem;

Screenshot 3: Booking Record

The victim shares the name of the fraudulent traveller.

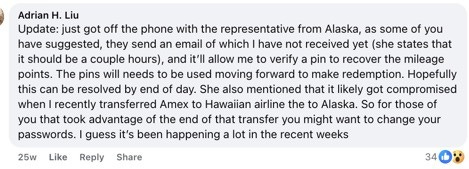

Screenshot 4: The Victim Shares Alaska Airlines Response

Exchange:

Tania McKeown: “Did they catch the person who did this?”

Adrian H. Liu: “nope. There was nothing they could do, unfortunately.”

Outcome: The fraudulent passenger entered the United States on a ticket procured through organised crime. No law enforcement coordination occurred despite hours of advance notice, a known US port of entry, and a named passenger.

What This Case Demonstrates

1. Alaska Airlines had advance notice of fraudulent international travel to the United States.

2. The victim explicitly requested law enforcement involvement.

3. Alaska possessed the fraudulent passenger’s name and booking details.

4. Multiple hours remained before the passenger would clear US Customs at Houston.

5. Alaska declined to coordinate with CBP or any law enforcement agency.

6. The customer service representative indicated awareness of a broader security issue affecting multiple accounts.

7. The fraudulent passenger entered the United States without interdiction.

Appendix B: ALK’s Disclosure

Virgin Trademark Litigation

Alaska acquired Virgin America in 2016 for $2.6 billion. As part of the acquisition, Alaska entered into a trademark licence agreement with Virgin Enterprises, granting Alaska the right to continue using the Virgin America brand. The agreement required Alaska to pay minimum annual royalties through 2039.

Alaska ceased making royalty payments in January 2020. Virgin Enterprises sued in 2019, seeking enforcement of the minimum royalty provisions.

The dispute was not complex. It turned on contract interpretation: did the licence require continued royalties regardless of whether Alaska used the brand? Virgin said yes. Alaska said no.

Trial occurred in October 2022. The court ruled for Virgin in February 2023. Alaska appealed. The appeal failed in June 2024. Alaska now owes approximately $200 million in royalties through 2039.

What the Table Shows

The table below tracks Alaska’s disclosures against the factual position across twelve quarters. Note:

No disclosure whatsoever until Q3 2022, three years after the lawsuit was filed and after trial had already occurred

The phrase “without factual and legal merit” repeated for five consecutive quarters, including after an adverse judgment

No accrual recorded until the final appellate loss, sixteen months after the initial adverse ruling

Even after liability became certain, disclosures quantified only past-due amounts, never the fifteen-year forward obligation

This is not a GAAP violation. It is something more carefully constructed: disclosure that is technically defensible but systematically misleading. No investor reading the successive disclosures, even today, would ascertain that the court case with no legal or factual merit had cost ~$200 million in payments, in addition to legal bills which likely have crossed over $10 million litigating this claim.